Educators urged to ‘rethink reality’ as XR augurs hybrid theatre, interactive broadcasting and virtual choirs

The leaders of a Cambridge graduate study programme exploring Extended Reality (XR) in arts education suggest that the technology should be at the forefront of wider educational research, given its transformative potential.

‘Extended Reality’ encompasses digital technologies that bridge the virtual and physical worlds. Academics at the University of Cambridge suggest that a number of recent projects, testing its potential for teaching in the arts, hint at a future where it may become commonplace in schools and universities. XR, they argue, opens up entirely new ways of teaching in digital space, creating a more dynamic and immersive experience that goes far beyond merely running lessons on Zoom.

Several student-led projects at the University’s Faculty of Education have shown that XR can be used for forms of learning that many teachers would consider impossible without face-to-face interaction. They include a successful mixed-reality theatre production; a digital 3D auditorium for hosting remote singing rehearsals, and a virtual space where users can ‘walk’ among the visualised contents of podcasts.

Mixed-reality experiences like these, researchers suggest, are likely to become routine features of young people’s cultural lives. At present, however, both academic and public discussion about XR focus on its applications in science and gaming. Its potential in education has barely been considered.

Singing, theatre and dance are disciplines in which being present, and the role of the human body, are paramount. Our younger researchers are now completely reshaping our conception of what you can do with those subjects in digital space.

The Cambridge studies emerged from a graduate course in Arts, Creativities and Education, led by Dr Annouchka Bayley. “Most educators are aware that we need to think more deeply about how to teach in a digital age; lockdown was serious wake-up call in that regard,” she said. “Until now, though, most of the discourse has been about how to take traditional classroom techniques and put them online.”

“With the arts, you’re in different territory, because things like singing, theatre and dance are disciplines in which being present, and the role of the human body, are paramount. Some of our younger researchers are now completely reshaping our conception of what you can do with those subjects in digital space. When you ravel that back to desk-based subjects like English and maths, you suddenly find that as a teacher you’re working with a completely new palette of possibilities and ideas.”

A number of Bayley’s students started to engage with mixed reality during the COVID-19 lockdowns. With university buildings temporarily closed, Dr Eleanor Dare, who lectures on the course, arranged for the group to meet in Mozilla Hubs: a collaborative tool for building virtual worlds. “Very quickly a number of students got in touch asking if they could do more to explore its educational potential,” Dare said.

In one early experiment, students created a digital stage to perform Brecht’s Life of Galileo using avatars. “The exercise immediately raised questions about how we should move and speak in digital space, and demonstrated how VR enables approaches you can’t take in a classroom or lecture theatre,” Dare said. “It suddenly becomes possible to stage a play on the beach, for example, or in a different time.”

Several students have since devised their own practice-based research projects using XR technologies. One is Jing Wang, who created an immersive, interactive performance piece based on Michael Frayn’s play, Copenhagen.

The play deals with the mysterious 1941 meeting between the famous physicists, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, whose work paved the way for the first atomic bomb. Wang’s research examined digital ways of teaching ethics of science in doctoral level ‘hard sciences’ degrees, in particular how creating mixed reality arts might deepen students’ appreciation of the complex themes of science, morality and the unrealisability of human intentions. “Most performances just focus on the story,” she said. “I wanted to bring it closer to our present.”

At its premiere last year, two Cambridge physics students played the roles of Heisenberg and Bohr from behind a glass screen, while the audience used earbuds to ‘eavesdrop’ on their conversation. They were then given access to a VR exhibition space that Wang had created, containing information about the two scientists’ real-life relationship, to explore at their own pace.

Her immersive approach had a profound impact on the young physicists involved. “The way we define physics is inorganic,” the student playing Bohr reflected. “We don’t normally consider that it has some form of life, or some sort of impact on people.”

Bayley agrees that Wang’s treatment helped to foreground the ethical dimensions of scientific research. “Ethics is notoriously difficult to teach in science because it challenges the premium on objectivity,” she said. “Jing bridged that gap by getting scientists to co-develop her mixed-reality performance.”

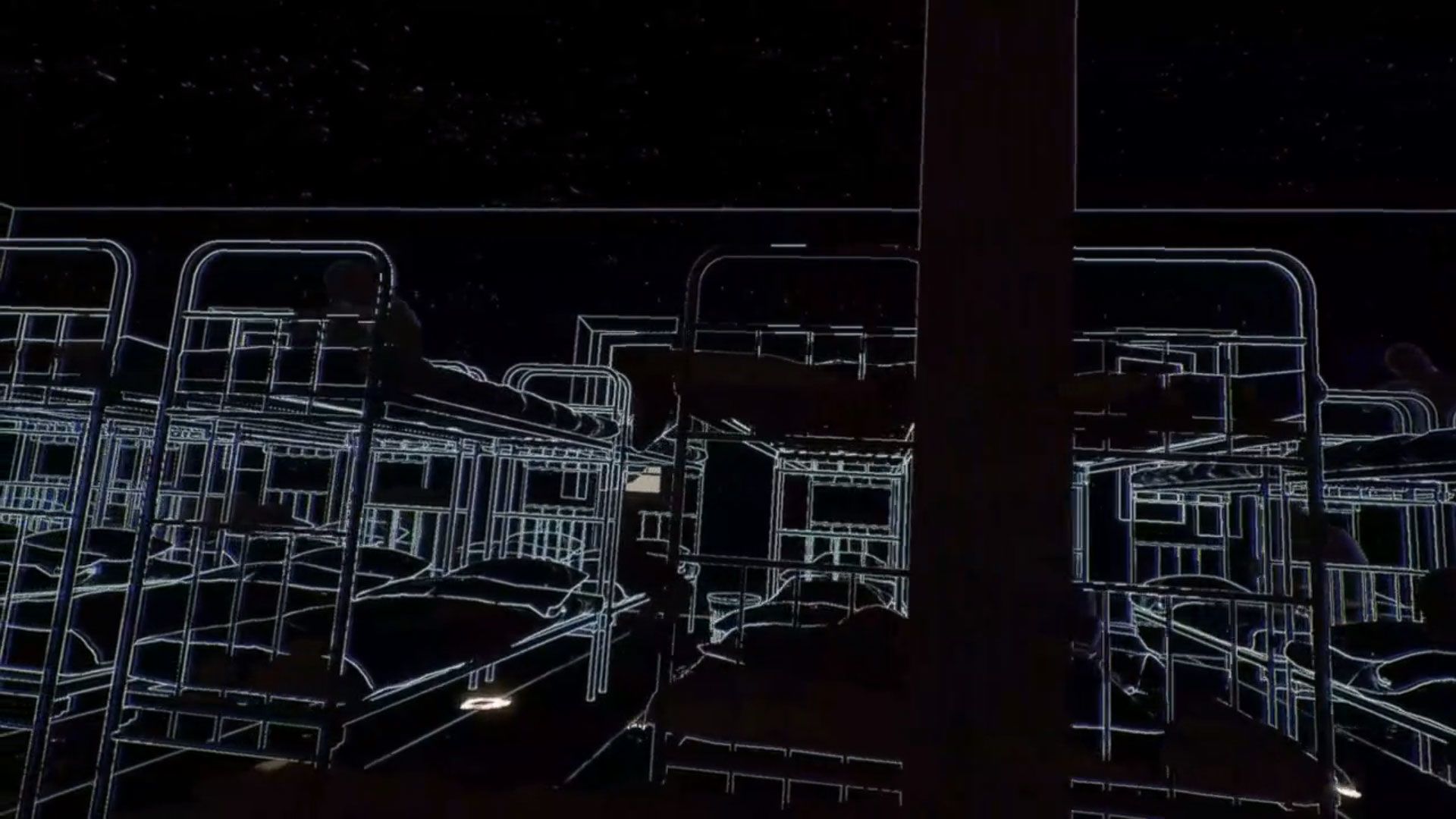

Wang’s interpretation of Copenhagen was also accepted by the Prague Quadrennial 2023. She is now developing another immersive experience based on Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. Messiaen composed the piece while a prisoner of war, and it was famously premiered in the Stalag VIII-A camp in Poland. Her VR version brings this context to life by placing audiences ‘inside’ the camp. As the music plays, they walk through its barracks and among ghostly prisoners and guards who seem to materialise from the surroundings.

Still from Jing Wang's VR experience accompanying Quartet for the End of Time.

Still from Jing Wang's VR experience accompanying Quartet for the End of Time.

Technology can be a bridge through which students from different settings share music and art. Through that, they might also understand each other better.

In a separate project, doctoral researcher Yaxin Li created a digital auditorium to explore the potential of Virtual Reality in music education. Musicians can perform live and record as avatars in a virtual environment she calls the ‘Hub-We-Verse’. The platform creates a realistic sense of depth and space: sounds become louder as the user approaches, and quieter as they move away.

Li, a singer who trained at the China Conservatory of Music, invited five conservatory-level students to use this virtual hub. They discovered novel ways of interacting, such as recording together and then returning later individually to practise with the recorded ‘group’.

She is now lecturing on these methods at the Conservatory, while completing a part-time PhD at Cambridge. XR could, she believes, democratise music education by widening access high-quality lessons. “Music education can be hugely expensive,” Li said. “The hub shows musicians that we can find ways to challenge its inequalities and share our resources more widely, if we want to.”

Students also seem to use the Hub-We-Verse to experiment more – an issue which is important to Li given the restrictive, top-down teaching that often characterises higher music education. She suggests that there are exciting opportunities for students from around the world to collaborate on projects as if they were together. “Technology can be a bridge through which students from different settings share music and art,” Li said. “Through that, they might also understand each other better.”

Inside Yaxin Li's 'Hub-we-verse'

Inside Yaxin Li's 'Hub-we-verse'

We are already moving from a stage of early adoption to one where extended reality technologies are more mainstream. That raises possibilities and challenges that warrant wider scholarly attention.

Other projects have taken a similarly imaginative approach to XR. One research student created a podcast by recording conversations with her colleagues while walking the streets of Cambridge. She then combined the audio with photographs from the walk in a virtual, 3D environment. Users can ‘travel’ among the images while the recordings play back.

The approach demonstrates how the technology can capture people’s inner experiences, but it also highlights how it might bring lessons to life differently in educational settings. Virtual Reality could, for example, be similarly used to place students ‘inside’ a historical site, and combine that visualisation with source materials from their lessons.

Dare’s research points to further, exciting opportunities with younger learners. In a project called the Future of Broadcast, in collaboration with the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, she and Dr Dylan Yamada-Rice worked with 200 children aged seven to 11 to create real-life models for virtual worlds. The children learned to scan their models using a photogrammetry app and the resulting assets were animated in VR, AR and the gaming platform, Roblox.

Dare observes that the children’s interactions with these creations resembled the ‘Ikea effect’, whereby we value something more when we have made it ourselves. She believes that children’s entertainment – an important but often undervalued learning space – will increasingly involve co-creation and non-linear storytelling where children are, similarly, active participants.

Characters created for The Future of Broadcast project (Dylan Yamada Rice and Eleanor Dare)

Characters created for The Future of Broadcast project (Dylan Yamada Rice and Eleanor Dare)

At one level, there are opportunities for educators to meaningfully incorporate similar techniques into learning. Dare also points out, however, that teachers need to be able to help children use the technology appropriately, given the challenges it raises in terms of data privacy, security and the environment. Similarly, she highlights the need for educators to investigate XR’s possibilities and limits in a range of other subject areas: whether bringing plays to life in English Literature lessons, exhibiting art in virtual galleries, or making music in VR ensembles.

“We are already moving from a stage of early adoption to one where extended reality technologies are more mainstream, and that raises all sorts of possibilities and challenges that warrant wider scholarly attention,” Bayley added. “Through arts-based research, we are starting to see how they allow students and audiences to experience different ways of learning, understanding and knowing. In a polarised world, that’s a very big deal.”