Memes-field Park? ‘Digital natives’ are flirting with Jane Austen’s vision of the ideal man all over again

In a newly-published analysis, literature specialists examine the phenomenon of internet memes about Jane Austen and her fictional creations, in particular those from Pride and Prejudice and, above all, Mr Darcy.

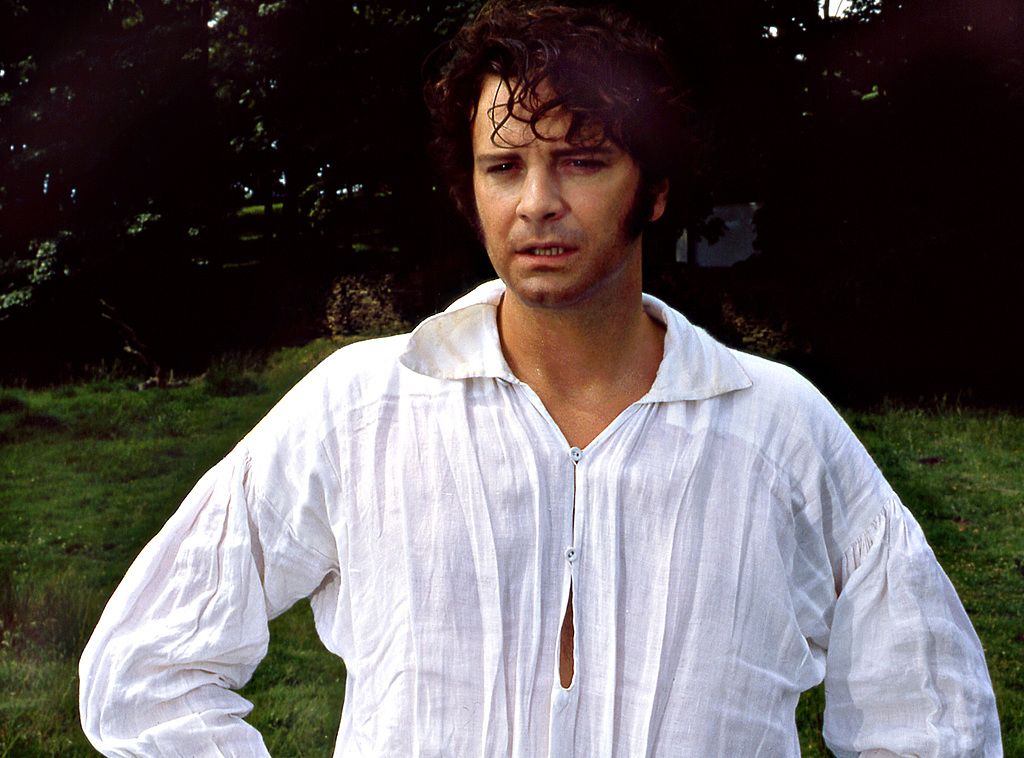

Know about the Darcy hand-flex? Remember that lake scene with Colin Firth? For 200 years, audiences have been swooning over different portrayals of Mr Darcy, Jane Austen’s iconic male hero. Now, he and Austen’s work in general are experiencing yet another rebirth: this time as the ‘meme idols’ of ‘digitally native’ millennials and Generation Z.

In a newly-published analysis, literature specialists examined the phenomenon of internet memes about Jane Austen and her fictional creations, in particular those from Pride and Prejudice and, above all, Mr Darcy.

Austen’s work is ‘memed’ – turned into bite-sized, ironic snippets of online content – more than almost any other author of classic fiction. Darcy alone features in hundreds of memes on social platforms like Pinterest and Tumblr, most of which draw on two famous portrayals: by Colin Firth in the 1995 BBC series of Pride and Prejudice and Matthew MacFadyen in the 2005 film.

Moments from both are relentlessly recycled by online content creators, the study observes. One example, clipped from Firth’s famous ‘lake scene’, claims: “A truth universally acknowledged: you either love Colin Firth as Mr Darcy, or you’re wrong”. Another repurposes a well-known meme template of Wolverine, from the Marvel X-Men comics, to show the muscular superhero pining over MacFadyen’s famous ‘hand-flex’ – which is sometimes regarded as the steamiest scene in cinema.

The study suggests Austen has become a social media phenomenon for two main reasons. One is that her books effectively contained memes-in-waiting before the concept existed. The other is that younger generations are reappraising traditional ideas about masculinity in the wake of high-profile sexual abuse cases, such as those highlighted by the #MeToo movement. Darcy, the authors of the analysis argue, has become emblematic of an alternative ‘ideal man’: a strong, yet sensitive, reformed hero who learns to control his emotions to positive ends.

The idea for the study came from two Greek scholars – Professor Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki) and Dr Maria Vara (Athens School of Fine Arts) who had previously contributed to a book, The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe and continued to follow trends in how her novels are consumed by modern audiences. Georgios Chatziavgerinos, a doctoral researcher at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, who is researching representations of masculinity in media, joined the study after inundating his two co-authors with the latest Austen memes on social platforms.

"Austen is probably second only to Shakespeare in terms of how much this happens with her work."

“Lots of authors are memed, but Austen memes have become a cult of their own,” Chatziavgerinos said. “A whole generation of young adults have grown up in a digital world where they use this sort of content to bond over shared values. Among classic authors, Austen is probably second only to Shakespeare in terms of how much this happens with her work. We wanted to understand why.”

As other researchers have explained, memes often enable fans of a particular artist or genre to discuss and satirise contemporary life through the prism of fandom. The study argues that the big themes in Austen novels – such as love, marriage, codes of behaviour, and private desire – provide ideal material through which younger audiences can discuss ideas about masculinity and femininity, sexual consent and non-conformity.

At one level, this is nothing new. Darcy’s brooding ‘alternative masculinity’, and the way he is motivated by his love for Elizabeth Bennett to become a better version of himself, has long provoked the sort of fan-worship that, for example, prompted ‘Darcymania’ around Firth in the 1990s.

The quantity of memes alluding to Darcy’s complexity, inner struggles and vulnerabilities has spiked in recent years, however. MacFadyen’s celebrated, electrified hand-flex after meeting Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth Bennett for the first time in the 2005 movie, for example, now has its own dedicated blog on Tumblr. Fans often contest which of Firth and MacFadyen was better: one post by the Jane Austen Centre, accompanied by the caption, “He may be Darcy… but I was Darcy Firth”, provoked thousands of responses on Facebook.

"Memes are cultural replicators that give audiences mini-bursts of irony. Austen’s writing foreshadows this because she often recontextualised other work to tell new truths about society."

The study’s authors suggest that Darcy’s hidden depths have acquired new meaning since #MeToo exposed the extent to which women experience harassment and sexual assault, especially from men in positions of power. “It’s no coincidence these memes skyrocketed after #MeToo,” Chatziavgerinos said. “Darcy, who balances conventional male qualities with sensitivity and respect for women, is in many ways the perfect antidote to the male behaviour that legitimately prompted such outcry.”

More generally, the study suggests that Jane Austen is highly memeable because she was doing something very similar in her books to what memes do today. “Memes are cultural replicators that give audiences mini-bursts of irony,” Kitsi-Mitakou said. “Austen’s writing foreshadows this because she often recontextualised other work to tell new truths about society.”

"Northanger Abbey hovers between authenticity and fakeness much as Austen memes do"

A good example is Northanger Abbey’s parody of Gothic novels, which were wildly popular in Austen’s lifetime. Austen sent up these books’ penchant for dark and stormy nights and damsels in distress, and in particular the social stereotypes they encouraged.

Some scenes in the book were absorbed by Regency audiences much as memes might be now, the study argues. One moment in which the heroine, Catherine Tilney, opens a suspicious chest she expects to be full of secrets, only to find an old laundry list, has itself become the basis of a popular meme about frustrated expectations.

“Northanger Abbey hovers between authenticity and fakeness much as Austen memes do,” Vara said. “There’s the same playful fakery, the same slightly ironic nostalgia.”

The study’s authors suggest that, like the TV and film adaptations before them, Austen memes are “seducing” a new generation of “non-Janeites” into her world through a new medium.

“Obviously I’d urge everyone to read the books, but what’s interesting is that often you need to have done so in order to really understand these memes,” Chatziavgerinos said. “Memes are now becoming one of the main ways in which younger audiences discover Jane Austen. They are breathing new life into her work and further cementing her immortality as a writer.”

The study is published in the journal Humanities.

Images in this story:

Colin Firth in the 1990s version of Pride and Prejudice

Firth and Jennifer Ehle in the same series

Both © BBC Archive, reproduced under an Academic Use licence.