Worldviews in the RE classroom: Game-changer or “spurious” RE-brand?

The idea of reframing Religious Education around the concept of ‘worldviews’ has provoked intense debate in the sector in recent years, following a 2018 report which proposed its formal integration into RE. Studies and associated discussions at the Faculty of Education have been trying to understand the proposal, the controversy, and determine how far it should define the future of RE in schools.

In September 2018, several national media outlets suddenly reported that atheism was about to become part of Religious Education. This was inaccurate – in fact, secular philosophies have, for decades, been taught alongside religious ones in schools.

The story had been sparked, however, by new recommendations published by the Commission on Religious Education, following a review of RE provision in English schools. In truth, this was making a much more complex proposal: to remodel RE by making ‘worldviews’ the central concept. The Commission defined a worldview as: “a person’s way of understanding, experiencing and responding to the world”, and it mentioned alongside this “worldviews” such as secularism and atheism.

Within education, this concept of a ‘worldviews framework’ has been stoking debate ever since.

Some see it as key to revitalising RE and reversing its gradual disappearance from school timetables. Others regard it as a hollow rebrand – or, in the views of one critic, “pernicious nonsense” – and have questioned what it actually means.

Last month, the Faculty of Education hosted a discussion aimed at untangling the worldviews concept and understanding why it has proven so controversial. It was organised Dr Daniel Moulin, who leads the University of Cambridge PGCE in Religious Education, and has also contributed to a new book, Religion and Worldviews, which questions the educational value of the worldviews approach. The main speaker was Professor Trevor Cooling, who contributed to the development of the framework, although he was speaking in a personal capacity. Cooling’s publications on the subject include the report Worldviews in Religious Education.

"It gives us a rejuvenated vision for RE in schools. It also provides a different view of the nature of the knowledge we are teaching in the subject, and a fresh understanding of the pedagogy we use in the classroom"

Professor Trevor Cooling

"The worldviews approach is really putting the subject’s coherence at risk. It’s hardly surprising that nobody wants to study RE if everything just becomes a matter of perspectives, rather than getting closer to understanding the reality of others’ lived experiences."

Dr Daniel Moulin

Cooling regards the worldviews concept as potentially “game-changing”. “It gives us a rejuvenated vision for RE in schools,” he said. “It also provides a different view of the nature of the knowledge we are teaching in the subject, and a fresh understanding of the pedagogy we use in the classroom”.

Moulin is more cautious and his recent book chapter offers a robust critique. He argues that the worldviews framework is a reheated idea which, partly because it assumes everyone has a system of beliefs or ‘personal worldview’, fails to pay due respect to the diversity and beliefs of pupils.

Worldviews in the RE Classroom: Watch the presentation by Trevor Cooling

Worldviews in the RE Classroom: Watch the presentation by Trevor Cooling

Speaking about his recent analysis, Moulin said: “The worldviews approach is really putting the subject’s coherence at risk for the obvious reason that not everyone is able to say that they have a fixed worldview: not least religious adherents or young people who are still working out what they think about the world. It’s hardly surprising that nobody wants to study RE if everything just becomes a matter of perspectives, rather than getting closer to understanding the reality of others’ lived experiences.”

In his lecture, however, Cooling rejected the suggestion that he was arguing that everyone has a fixed worldview, or that RE was just a matter of perspectives. He accepted in the discussion that perhaps the word ‘worldview’ was potentially confusing and not truly indicative of his position.

Despite their (amicable) differences, both academics agree about many of the underlying principles which drove the framework’s conception. In particular, they argue that the subject needs significant reform and to reach beyond what is known as the ‘World Religions’ approach, in which teachers essentially focus on helping students to absorb and retain information about different religious traditions.

The need for reform is also implied by RE’s diminishing status in some schools. Many academies and free schools, which do not have to follow locally-agreed syllabuses, have chosen to cut back on it. According to the National Association of Teachers of Religious Education, almost 500 schools reported no timetabled RE for 14 to 16-year-olds in 2021. Parliamentarians have called for a new national plan to address this. The worldviews framework was meant, in part, to offer exactly that.

More than four years later, some scholars feel that what it means, and how it should be practised, is so difficult to pin down that it is failing to gain traction. Cooling, however, highlights work being undertaken by the REC to write a curriculum based on the concept.

When it comes to defining worldviews, Cooling suggests that broadly it is about focusing RE on the exploration of how humans differ in their views, why they do and how they can dialogue about those differences and make reasoned and informed judgements as to their truth. He also thinks that the Commission’s early attempt at definition didn’t exactly help, because it conflated institutional worldviews (like atheism) with personal perspectives. “What we’re really interested in is an individual’s personal way of understanding the world: a filter through which we experience and interpret information and thereby generate personal knowledge of what’s around us,” he said.

A better explanation, he suggests, was offered by the Theos think tank in their short video, Nobody Stands Nowhere. As the title suggests, this advances the idea that RE should help students to learn that in any debate, people enter the discussion with a set of assumptions and commitments. We sometimes call these credos, prejudices, or control beliefs – to mention just a few terms. The Commission Report calls them “personal worldviews”.

Moulin, however, says that a shift in RE teaching based on this idea is flawed because it uses old ideas to address long-standing problems: how to make young people feel religion is worth studying, how to avoid promoting specific viewpoints over others, and how to negotiate contested beliefs in the RE classroom.

Teaching children about worldviews, for example, was first advocated in 1979. Moulin is also concerned that the framework addresses these challenges selectively and privileges some solutions over others, making it, he writes, “no less spurious or discriminatory than earlier attempts” to fix RE’s “Cinderella” status in schools.

“Worldviews is a reasonably useful term, in that we need a vocabulary to talk about non-religious traditions, values and cultures, but I think it is also an insufficient term and a confusing one”, he said.

“As a concept it doesn’t seem to engage with the reality of what people are actually doing when they participate in religion and the resonance this might have. I struggle with the idea that everyone has a personal belief system when most people’s lives don’t reflect that.”

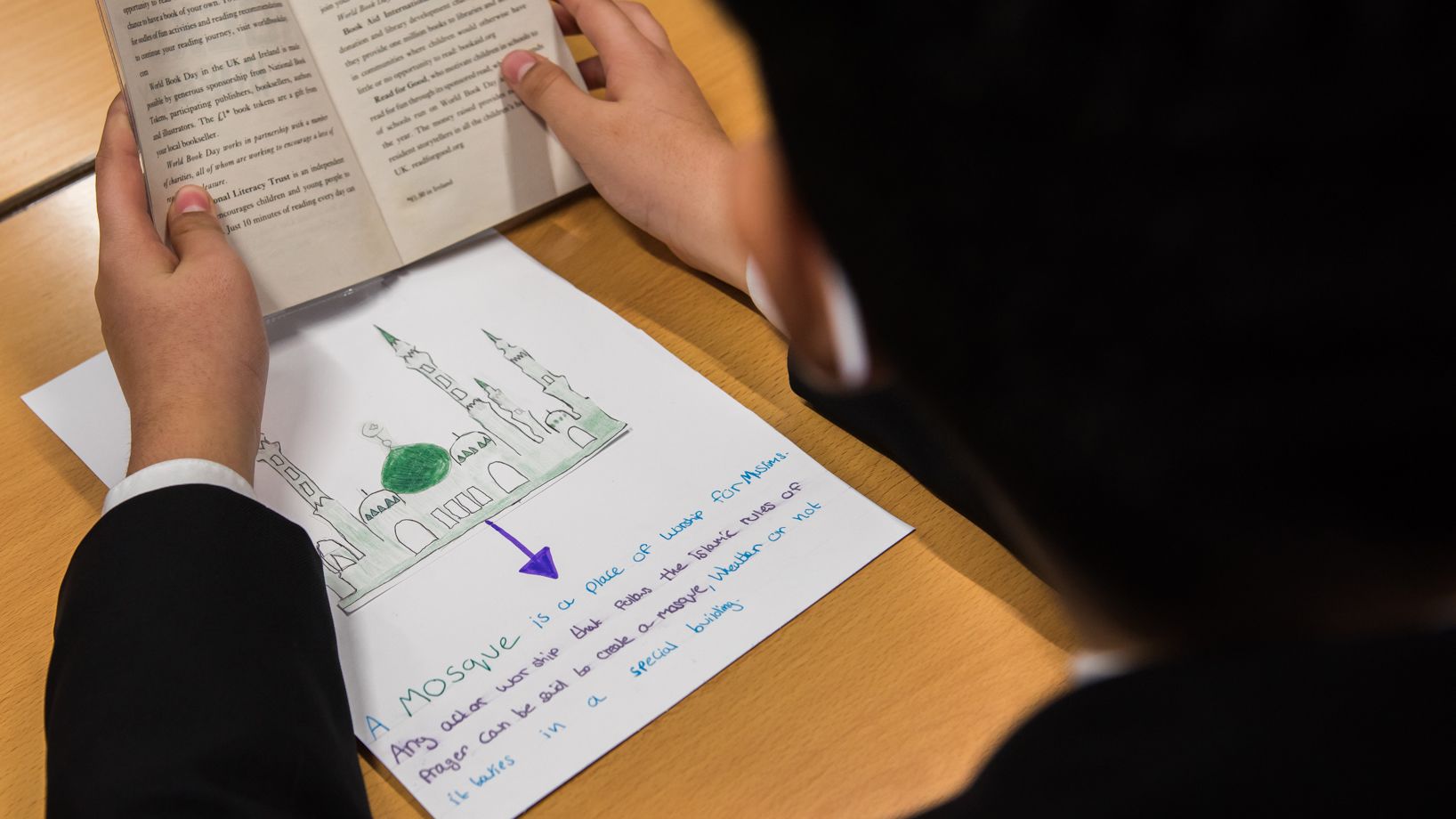

“More importantly, different traditions understand and refer to themselves distinctly - using their own terms that reflect their different epistemologies which are often quite different from that implied by the Western notion of a ‘worldview’. Islam, for example, is about submission to the one, true God. That’s not just someone’s view of the world; it’s part of it. To insist that any given religious tradition is someone’s worldview risks patronising it and potentially glosses over their own lived reality.”

Cooling makes a number of points in response. Firstly, he stresses that the Commission’s 2018 report was not the finished article but the start of a process of continual refinement. Since 2018, there has been a literature review and a third report which tried to capture the scholarly consensus about what worldviews and their implications for the classroom. Further work is being undertaken with a spectrum of schools examining how the approach translates into the curriculum.

He agrees with Moulin that there are dangers in using the word, ‘worldview’, but argues that it is the best available to capture the approach being proposed – and adds that he would welcome other suggestions. This underlines the fact that, in Cooling’s view, worldviews should not be seen as a one-size-fits-all model for teaching RE. Rather, as Amira Tharani put it in a report commissioned by the REC, it is a ‘can opener’ concept which unlocks the content of the curriculum.

He suggests that examining both religious and non-religious perspectives through the lens of worldviews invites young people to take a hermeneutical, or interpretative, approach to studying them. In effect, it invites them to become not just students of religion, but scholars of it, capable of making informed judgements with a sense of where different perspectives come from.

He also thinks that this will encourage skills such as self-reflection and the ability to listen to and empathise and differ well with others.

“We seem increasingly to inhabit this culture wars climate in which it doesn’t matter what you say, so long as you knock others down,” Cooling said. “I think that RE has something to say about that, and the worldviews framework helps us in that regard.”

"We badly need a different type of Religious Education: one that engages with religious and non-religious ideas and addresses the big things young people really care about – like what kind of people they want to be, and what kind of world they want to live in."

Dr Daniel Moulin

"I think Daniel’s overall assessment of what’s needed is very good. I just don’t agree that it leads to negative conclusions about the worldviews approach."

Professor Trevor Cooling

Moulin believes that, however flexible the framework claims to be, relying on a single starting point when teaching RE is not the way to make the subject meaningful in schools.

He says that teachers should draw flexibly on different educational models and different religious traditions, in a curriculum which focuses on helping young people to navigate ideas about ethics, values and what it means to ‘live well’ – and tackle pressing challenges such as racism, prejudice and climate change.

“We badly need a different type of Religious Education: one that engages with religious and non-religious ideas and addresses the big things young people really care about – like what kind of people they want to be, and what kind of world they want to live in,” he said. “Schools that recruit teachers capable of taking that approach have no trouble making RE appeal to students.”

“This isn’t helped if we assume that one only has a view of the world, or that we should study the view and not the world itself. Religious education has to go beyond the superficial study of the beliefs of others to encourage students to engage deeply with sources of wisdom in religious and non-religious traditions that continue to inspire people of all faiths and none to act for the common good. To stop at worldviews limits that possibility of pursuing and utilising knowledge. Ultimately, it won’t lead to a deep and fulfilling life.”

Cooling suggests that he “couldn’t agree more with Daniel’s points” in this area and feels that their perspectives, particularly as they strive to move beyond more conventional ways of teaching RE, are not worlds apart. “I think Daniel’s overall assessment of what’s needed is very good,” he said of Moulin’s recent book chapter. “I just don’t agree that it leads to negative conclusions about the worldviews approach.”

Daniel Moulin’s article, “‘Religion’, ‘worldviews and the reappearing problems of pedagogy” appears in the Routledge publication, Religion and Worldviews: The Triumph of the Secular in Religious Education. For more information about the worldviews framework, visit the Religious Education Council website.

Images in this story:

Globe image by Greg Rosenke on Unsplash.

Image of religious symbols by Noah Holm on Unsplash

Other images owned by Faculty of Education