Focused interventions for girls with disabilities fuelled ‘life-changing’ impact on aspirations and self-esteem

An evaluation of UK Government-backed education programmes in lower-income countries shows that interventions which deliberately target girls with disabilities can reach far beyond the classroom, potentially transforming their aspirations and self-esteem.

The newly-published report, led by academics at the University of Cambridge, is the latest in a series evaluating phase II of the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC): a UK Government initiative which aims to improve the lives of one million of the world’s most marginalised out of school girls by providing access to high-quality education.

Researchers assessed 41 projects in 17 countries across the Global South, involving over hundred thousand girls with disabilities (identified using the Washington Group questions), alongside other marginalised young women. 19 of these projects featured elements specifically tailored to the needs of girls with disabilities.

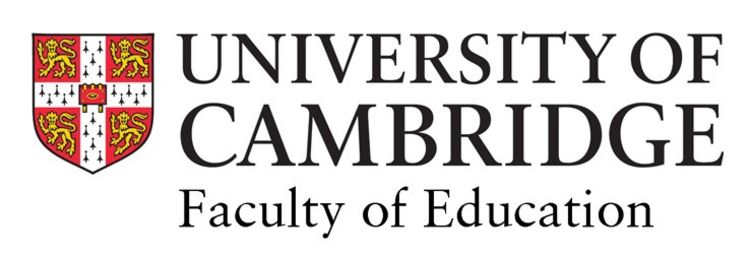

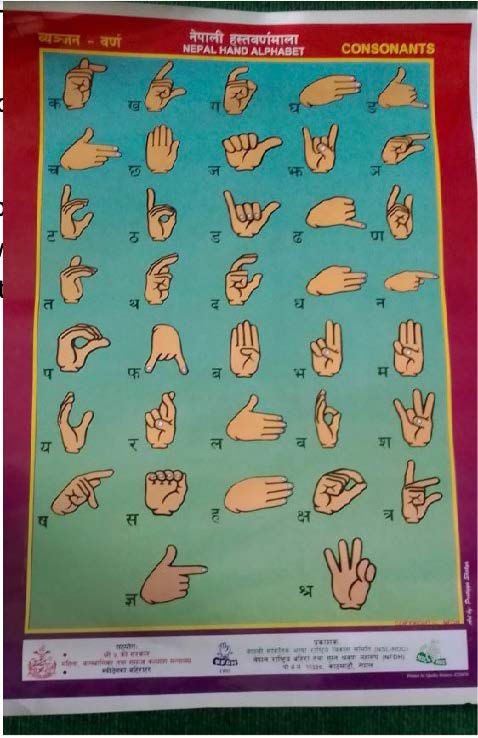

Nepali sign-language alphabet on a classroom wall, photographed by one of the project's student participants.

Nepali sign-language alphabet on a classroom wall, photographed by one of the project's student participants.

While the findings tentatively indicate that these interventions improved learning outcomes, the most striking results concern the broader social and emotional impact. Researchers recorded multiple cases of girls expressing greater confidence and self-esteem, improved social interactions, and more positive aspirations for their own futures. Some programmes that included vocational skills training had even helped girls to start businesses and acquire financial independence.

These promising results are qualified by over-arching concerns about persistent, basic problems with educational provision in many of the countries. Evidence from the girls who took part, for example, highlighted school buildings without adequate sanitation, or even desks and chairs. While these issues affected all pupils, they particularly disadvantaged those with complex needs.

Girls with disabilities count among some of the world’s most marginalised young people because of the “double disadvantage” they face from societal attitudes towards both women and people with disabilities, which often leads to inadequate educational support or resourcing.

One study of 51 lower and middle-income countries has estimated that only two in five girls with a disability finish primary school.

Evidence about how to address this is, however, relatively scarce. Where it exists, it tends to consider how interventions might improve access to education, rather than focusing on academic attainment and the wider impact on these girls’ lives.

Professor Nidhi Singal, from the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, said: “Many of the interventions we studied had led to transformations in the girls’ self-confidence, sense of empowerment, and their broader social interactions. The reason was that the projects in question had assessed the specific needs of girls with disabilities and put appropriate measures in place.

“It is critical that we develop more focused interventions for these marginalised young women. Doing so could make a real, lasting difference not just within the classroom, but far beyond it.”

The impact on their aspirations and sense of empowerment, as well as the faith it gave them in education, was really amazing.

The projects studied were run in 17 different countries and implemented a range of strategies to help girls with disabilities. These included specialised teacher training, the provision of assistive devices, infrastructure adaptations in schools and transport provision for students who might otherwise find accessing school difficult.

As well as evaluating data from all 41 initiatives, the researchers undertook three case studies in Nepal, Malawi and Uganda. To draw out the voices of the students themselves, girls were asked to take a photograph or record audio clips responding to various prompts, such as “What do I like about my school?” These then formed the basis of in-depth interviews.

There is some evidence that those programmes which featured elements tailored to the needs of girls with disabilities led to improved learning outcomes. In particular, students who participated in a specific set of initiatives within the GEC programme targeting the most marginalised girls, called ‘Leave No Girl Behind’, showed improvements in reading and numeracy.

The most significant results from the evaluation emerged from aspects of the GEC projects which looked beyond academic attainment alone. Programmes which incorporated a level of vocational education proved particularly impactful. A number of interventions taught girls with disabilities skills such as how to make and mend clothes, how to drive auto-rickshaws, or how to make their own jewellery. Several of these students had since started selling what they made, or even launched their own businesses.

As this implies, the programmes were often particularly successful when they incorporated training which presented girls with disabilities with a clear sense of how to build a secure and meaningful future for themselves. Students expressed enthusiasm about their newfound ability to contribute to household income, and shared aspirations to become teachers, farmers, bankers or beauticians. One student told her interviewers: “In the future, after becoming a teacher, I will teach deaf students like me.”

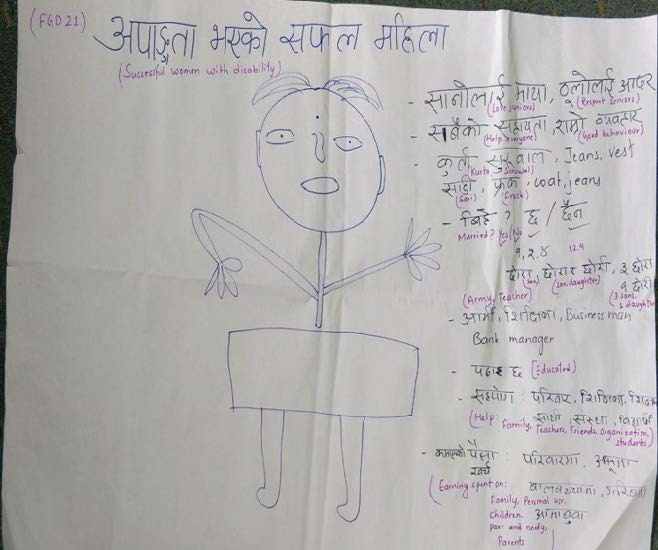

Image by student in Nepal asked to draw a "successful woman". The description reads: "She has a disability. But also, she talks like us. She loves younger people and respects elders. I told earlier she has studied, she writes poems. She does not have a hand. She publishes novels. She earns money."

Image by student in Nepal asked to draw a "successful woman". The description reads: "She has a disability. But also, she talks like us. She loves younger people and respects elders. I told earlier she has studied, she writes poems. She does not have a hand. She publishes novels. She earns money."

“My life has changed. I was a timid girl. I used to be shy. This has changed since I enrolled in school.”

The study also highlights the effectiveness of community based mentoring programmes.

In Nepal, one such initiative, called Big Sisters, invited older girls from the community to partner with girls with disabilities and provide both academic support and help with day-to-day tasks. As well as making the girls more self-sufficient, the approach, because it was embedded in the community, raised broader awareness about the importance of providing girls with disabilities with a meaningful education.

Students who participated in the GEC programmes often reported feeling less self-conscious both academically and socially. “My life has changed,” one girl in Malawi told the researchers. “I was a timid girl. I used to be shy… This has changed since I enrolled in this school.”

Dr Laraib Niaz, a postdoctoral researcher on the project, said: “The effects on the girls’ confidence were striking. This was particularly the case where girls received vocational training or took part in initiatives which increased their engagement with their families and communities. The impact on their aspirations and sense of empowerment, as well as the faith it gave them in education, was really amazing.”

Providing girls with additional resources or adaptations based on clearly identified and assessed needs also proved beneficial. Some projects, for example, equipped schools with resources for instruction in Braille or sign language. Another provided shoes, crutches and wheelchairs to girls whose physical impairments had previously prevented them from attending school at all.

The report stresses, however, that any such measures must be accompanied by more basic improvements to schools. Evidence from the students themselves often underscored the dire state of school infrastructure.

Unclean toilets posed a deterrent to girls with and without disabilities alike, particularly during menstruation. Girls in Malawi provided photographs of thatched classroom roofs and walls with holes in them. “If it starts raining while I am at home, I don’t go to school,” one elaborated. “If the rain starts in class we must hide in the corners. This does not really help because the whole roof is damaged and we usually get wet.”

Holes in a classroom ceiling, photographed by a student in Malawi

Holes in a classroom ceiling, photographed by a student in Malawi

Singal, who is also convener of the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER) emphasised the need to move beyond a “scattergun” approach to helping children with disabilities by focusing on assistive resources alone. “Giving someone Braille resources is no good if the teacher hasn’t been trained to use them; putting a ramp at the entrance to the school is no use if the classroom is overcrowded,” she said. “The lesson for policymakers is to consider the marginalisation of girls with disabilities as a distinct issue while simultaneously addressing broader, intersecting disadvantages. Disabilities should not be an afterthought; nor a second step.”

Read the full report here and the accompanying annexes here.

Images in this story reproduced from Evaluation Study 4 of the Independent Evaluation of the Girls' Education Challenge Phase 2.