Later Roman students were deliberately given “difficult” Latin as a passport to prestige

We might naturally assume that, compared with modern readers, ancient Romans found Virgil’s Aeneid relatively straightforward. According to new research, however, even students in Late Antiquity were expected to find literary Latin hard going, and learned it partly to differentiate themselves as the ‘cultured few’.

The analysis, by University of Cambridge academic Dr Frances Foster, argues that the ancient counterparts of today’s Latin students may well have wrestled with Latin poetry just as much as they do; finding the high register of authors like Virgil

Her study is part of a new volume on the “jewelled style”: an intricate form of Latin popular in Late Antiquity. Foster shows that students learned Virgil not just to grasp this style, but to emulate it. This, she adds, would have been as taxing for a Late Roman student as asking a modern English speaker to read and imitate Shakespeare.

Even for students at the start of the fifth century, Virgil’s Latin was meant to be difficult.

Roman students underwent these gruelling literary acrobatics not because they needed them for everyday conversation, but because Virgil’s higher register of the language conveyed prestige, the study suggests. Even before the fall of the western Empire in the fifth century, literary Latin was becoming part of a cultural ‘code’ that signalled elite status. The association with wealth and exclusivity is arguably one the subject still contends with today.

Foster, who researches ancient education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, examined sources that provide an insight into Roman teaching practice. Her study focused on Servius: a prominent intellectual who ran a school in Rome and wrote detailed commentaries on Virgil to help students understand the jewelled style.

“Even for students at the start of the fifth century, Virgil’s Latin was meant to be difficult,” Foster said. “A Roman learning the Aeneid would have been confronted with unfamiliar vocabulary, syntax and grammar. We tend to assume Roman poetry is hard because we don’t speak Latin, but it is a language like any other. If you want to discuss everyday issues, the language you need isn’t that complex. If you want to read Virgil, you are dealing with something that goes beyond even formal registers.”

“Servius was trying to bridge that gap because he knew that Roman students found it difficult to decipher.”

Coined by the scholar Michael Roberts in the 1980s, the ‘jewelled style’ refers to highly complex Latin poetry that used devices such as unconventional sentence structures, and precise yet vivid vocabulary, to create a detailed, ‘glittering’ linguistic effect.

The new book featuring Foster’s study shows how these principles were more prevalent across Latin literature than has previously been understood.

Foster cross-referenced Servius with other sources, notably Ausonius, a contemporary poet and teacher from Gaul, as well as the Colloquia, a set of dialogues used for ancient language learning and set in schools.

These show that the study of Latin literature was often oral, and that students were expected not just to understand the Aeneid, but perform parts of it, or even create their own compositions in the jewelled style, based on Virgil’s work. This required deep engagement with the verbal and visual patterns in his poetry.

Scholars have often noted that Servius’ Commentary on the Aeneid is unusual for its intense focus on specific minutiae or episodes. Foster argues that this makes sense when seen in its challenging educational context. Servius was not just trying to explain the Aeneid, she says, but to help students overcome their difficulties with its complex features so that they could replicate the style themselves.

Her study provides several examples of this. In his commentary on Book One of the Aeneid, for example, Servius undertakes a close examination of Virgil’s word choices regarding a coronet decorated with precious stones. His attentiveness to what seems a trivial feature of the text enables him to guide students through unusual vocabulary, and to show how Virgil used specific terms for pearls and gems to create a vivid mental picture for the reader.

Similarly, Servius dissects Virgil’s word choices for colours when describing a dawn scene in Book Seven. His analysis seems almost exhaustively microscopic, covering specific hues and shades, like “saffron yellow”, but it is, again, far from arbitrary. Virgil’s own writing was simultaneously trying to create a very precise polychromatic effect and making deliberate allusions to Homer. This created a potential minefield of misunderstandings for Servius’ students who, if they were to emulate the jewelled style themselves, would have to understand these minutiae.

Roman students probably found this advanced study as punishing as it sounds. The late Roman theologian, Augustine of Hippo, for example, once reflected that while he enjoyed the epic tales of the Aeneid during his schooldays, the accompanying linguistic analysis did not have the same allure. Previous research by Foster indicates that today’s students have similar views.

It was difficult to master, but it conveyed the social status and cultural sophistication that wealthy parents sought for their children.

Despite this, this type of education was highly prized. Servius’ school was a training ground for the Empire’s elite, drawing in young men from across its territories, including those who did not even have Latin as a first language, let alone command of the jewelled style.

Graduates typically went on to high-ranking positions. Even if they did not actively need the jewelled style for everyday communication, their written records reveal a proficient command of literary Latin. The contemporary poet Claudian, for example, who would have received a similar education, was court poet for the emperor Honorius. Foster describes his work as “more classical than Virgil”.

This suggests that a high-level Latin education was already a symbol of prestige even in Servius’ time. “The education that the Roman literary elite received equipped them with a highly stylised form of language,” Foster said. “It was not practical and it was difficult to master, but it probably conveyed the social status and cultural sophistication that wealthy parents sought for their children.”

Learning the Jewelled Style, by Frances Foster, appears in A Late Antique Poetics? The Jewelled Style Revisited, published by Bloomsbury.

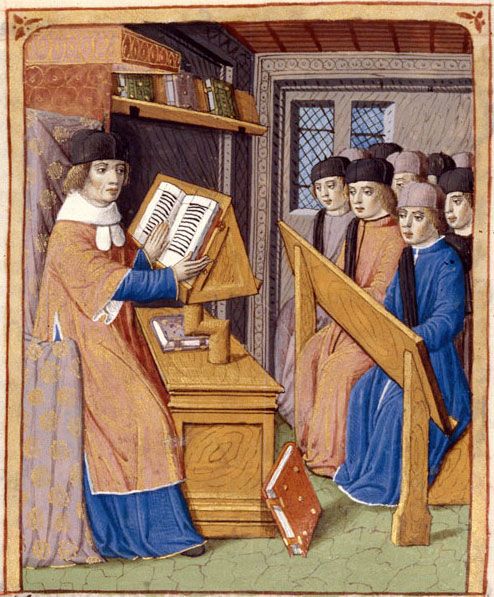

Images in this story:

15th century depiction of Servius teaching Virgil (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany - Funerary relief found in Neumagen near Trier, a teacher with three discipuli, around 180-185 AD, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier, Germany via Wikimedia Commons.