Citizens in the making

Inside the schools that prioritise ‘harmonious living’

A new ethnographic analysis of some of India’s most successful schools shows how their focus on cultivating ‘active harmony’, rather than traditional academic goals, may provide a template for the elusive challenge of teaching ‘citizenship’.

University of Cambridge researcher Dr Jwalin Patel spent 10 months living and working at five alternative schools in India which, viewed from a Western standpoint, adopt a very different – and often experimental – approach to education.

Pupils, for example, frequently have the freedom to decide what and how they learn; undertake fieldwork with NGOs and on farms, and are actively encouraged to challenge decisions about how their school is run. Despite the unconventional approach, all five institutions have strong academic records and are sought after by parents.

Patel, a postdoctoral researcher at Cambridge’s Faculty of Education, is studying how the philosophy which underpins this teaching and learning may provide a model for ‘Learning To Live Together’. ‘LTLT’ is a learning aim which the United Nations has set for education systems worldwide through its 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, but which schools often find difficult to conceptualise or implement.

“Ideas such as ‘togetherness’ and ‘education of the heart’ are vague and fuzzy. For many schools it ends up being little more than a tick-box exercise.”

Jwalin Patel

In the UK, for example, LTLT is often interpreted as meaning citizenship studies, socio-emotional learning, peace education (including the study of how to build more harmonious societies) or the study of civic responsibility and human rights. Because it sits apart from the core, academic parts of the curriculum, it often receives only perfunctory attention in the classroom.

“Part of the problem is that we still don’t really know what Learning To Live Together means,” Patel said. “Ideas such as ‘togetherness’ and ‘education of the heart’ are vague and fuzzy. For many schools it ends up being little more than a tick-box exercise.”

“In India, there are schools which may offer a way of resolving this because they focus on what we might call ‘active harmony’ – a way of living and being that we want children to acquire. It’s a very different approach to education, but one that we might want to understand if we are serious about meeting the educational goal of LTLT.”

The five alternative schools Patel studied were all founded or inspired by great Indian thinkers: Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, Jiddu Krishnamurti and Rabindranath Tagore. All four perceived the true purpose of education as developing qualities that make us human and give our lives meaning.

The schools also operate independently of Government, pursuing their own curricula and recruitment. Their approach appears to have achieved impressive results. Mirambika Free Progress School in Delhi, for example, appears in lists of the 100 best schools in India. Rishi Valley School in Chittoor, consistently ranks as one of the best boarding schools.

Patel embedded himself in the life of each school for several weeks, observing lessons and activities, and interviewing teachers and school leaders about their philosophy, what they saw as the purpose of education, and its implementation.

“Students become tolerant by conflict, by learning to know that you need not always be right... You cannot have an ‘it’s either my way or no way attitude’.”

Teacher interviewed during study

He found that they interpret LTLT as ‘harmonious living’. Specifically, this means developing pupils’ ‘personal’ harmony (for example, helping them to understand their emotions and what shapes them as individuals, and helping them to develop a level of inner peace); harmonious relations with others (by encouraging an appreciation of diversity and difference); and a sense of how, as citizens, they might contribute to creating a harmonious society.

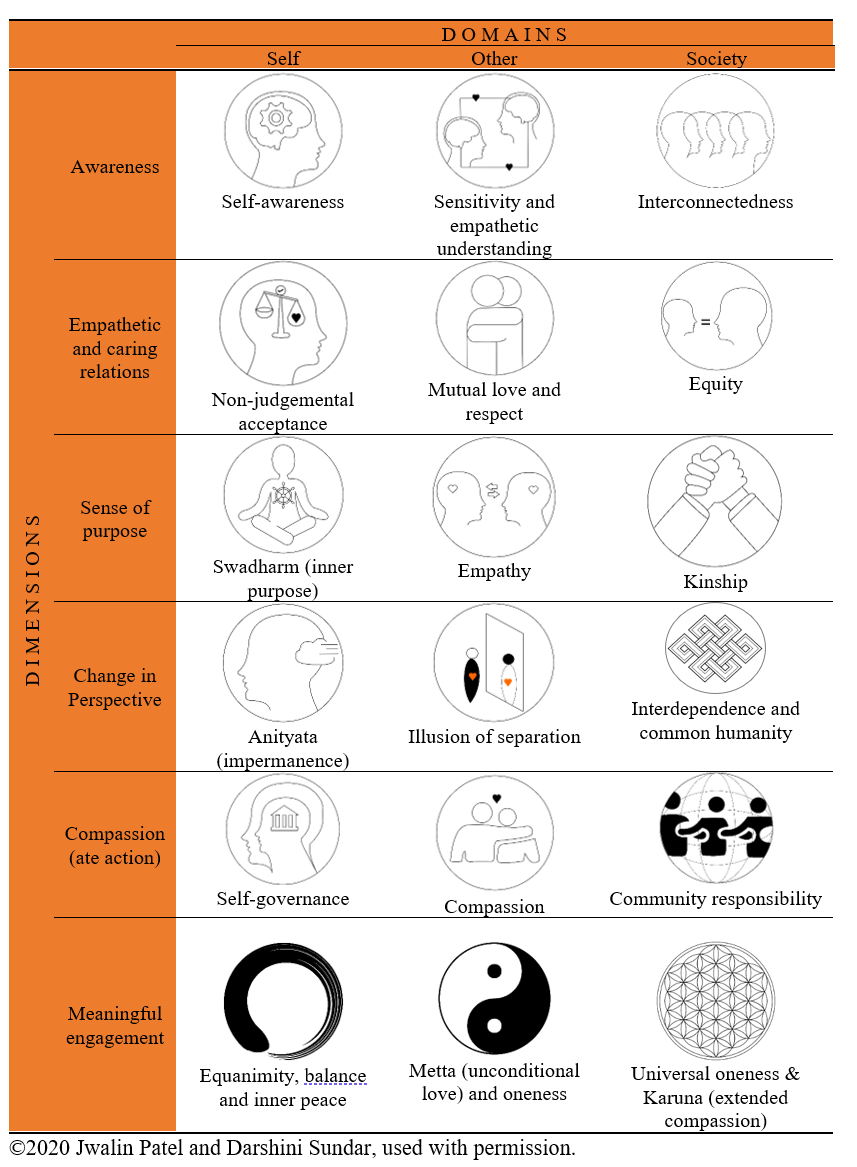

At a conceptual level, the research identifies six overlapping and mutually-reinforcing qualities, or dimensions, which teachers at all five schools try to instil in students . These are:

- Awareness: Empathetic understanding of others and appreciation of interconnectedness

- Caring relations: Mutual trust and respect, even with people who have different views. The ability to put oneself in another’s shoes.

- Sense of purpose: A commitment to achieving wellbeing and harmony, rather than simply acknowledging its importance.

- Changed perspective: A deeper understanding of people and the world, in particular appreciation of diversity, multifaceted identities, and interdependence.

- Compassion: Taking responsibility and action for the well-being of others through self-transformation, inner and external peacebuilding, and by addressing social injustice.

- Meaningful engagement: Harmonious behaviours resulting from engaging with others as equals, community responsibility and community living.

While the detail of how teachers seek to develop these qualities in the classroom will be covered in future publications, two initial articles by Patel provide an outline. For example, the schools’ learning programmes deliberately focus on social issues, developing pupils’ grasp of their interdependence with nature, and of the processes that shape their community. Teachers interviewed by Patel had arranged visits from local waste-pickers, craftspeople, mechanics and artists in an effort to deepen their students’ understanding of the different roles performed by people in their community. Pupils also spent time living on farms, participating in recycling initiatives, or fundraising for NGOs.

Each school also prizes collaboration over competition, which teachers regard as having the potential to erode self-esteem. Uniforms and academic streaming are generally avoided, as they run contrary to an appreciation of diversity and acceptance of others.

In addition, the research finds that the schools embrace Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha – determined, non-violent dissent to achieve social change – and related philosophies that encourage students to think critically about the social and political structures around them.

Respectful disagreement – including between pupils and teachers – is therefore treated as “a must”. Disputes and conflicts are often discussed openly in classrooms or school fora, with teachers guiding conversations using dialogic techniques to encourage dissent, mutual acceptance and collaborative decision-making. There is also extensive use of student councils, which debate everything from lunch menus to school policy. One teacher told Patel: “Students become tolerant by conflict, by learning to know that you need not always be right... You cannot have an ‘it’s either my way or no way attitude’.”

Such measures suggest that as well as trying to cultivate ‘harmonious living’, the schools deliberately operate as spaces where pupils encounter, develop and practise acts of compassionate citizenship – the approach Patel describes as ‘active harmony’.

“There are lots of small movements in different countries that are challenging conventional ideas about education and looking at what may be possible with Learning To Live Together.”

Jwalin Patel

Implementing such models of education on a national scale, either in India or other countries, would require a seismic shift in political will. Patel suggests, however, that these local examples of how LTLT might be made meaningful and operable could provide ideas and inspiration for individual schools, or clusters of schools, elsewhere.

“There are lots of small movements in different countries that are challenging conventional ideas about education and looking at what may be possible with Learning To Live Together,” he added. “Many Indian thinkers behind these alternative systems would argue that this does not start with Governments or a one-size-fits-all approach, but has to be a decentralised process, led by schools who retain the freedom to determine how students themselves learn.”

Two initial articles from Patel’s research on LTLT are available now in the Cambridge Journal of Education and Educational Philosophy and Theory.

Main image: Pupils at Mahatma Gandhi International School. Image reproduced under at Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Wikimedia Commons.