Project aims to close the postgraduate ‘offer gap’ for under-represented students

A new collaboration involving researchers, careers specialists and inclusive recruitment organisations aims to address the ‘offer gap’ in postgraduate admissions. The term refers to a gulf in application success rates which means too few people from historically marginalised, ethnic minority backgrounds are undertaking advanced study at British universities.

The project, which was originally announced at the end of 2021, is a joint venture between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but will also draw on the expertise of organisations outside Higher Education which work to improve fairness, inclusion and diversity in industry and the professions. The Faculty of Education, which is providing the academic leadership at Cambridge, is now recruiting to a research post on the four-year programme.

The project aims to ‘disrupt’ existing postgraduate selection processes and test alternative methods to enable more students from minority ethnic backgrounds to undertake postgraduate study and research, thereby potentially embarking on longer-term academic careers.

Postgraduate recruitment is more complex and varied than undergraduate admissions. While there is no evidence that existing recruitment processes deliberately favour or exclude particular types of student, the proportion of Masters and Doctoral students from minority backgrounds is significantly lower than that of White students, especially at leading universities, including Oxford and Cambridge.

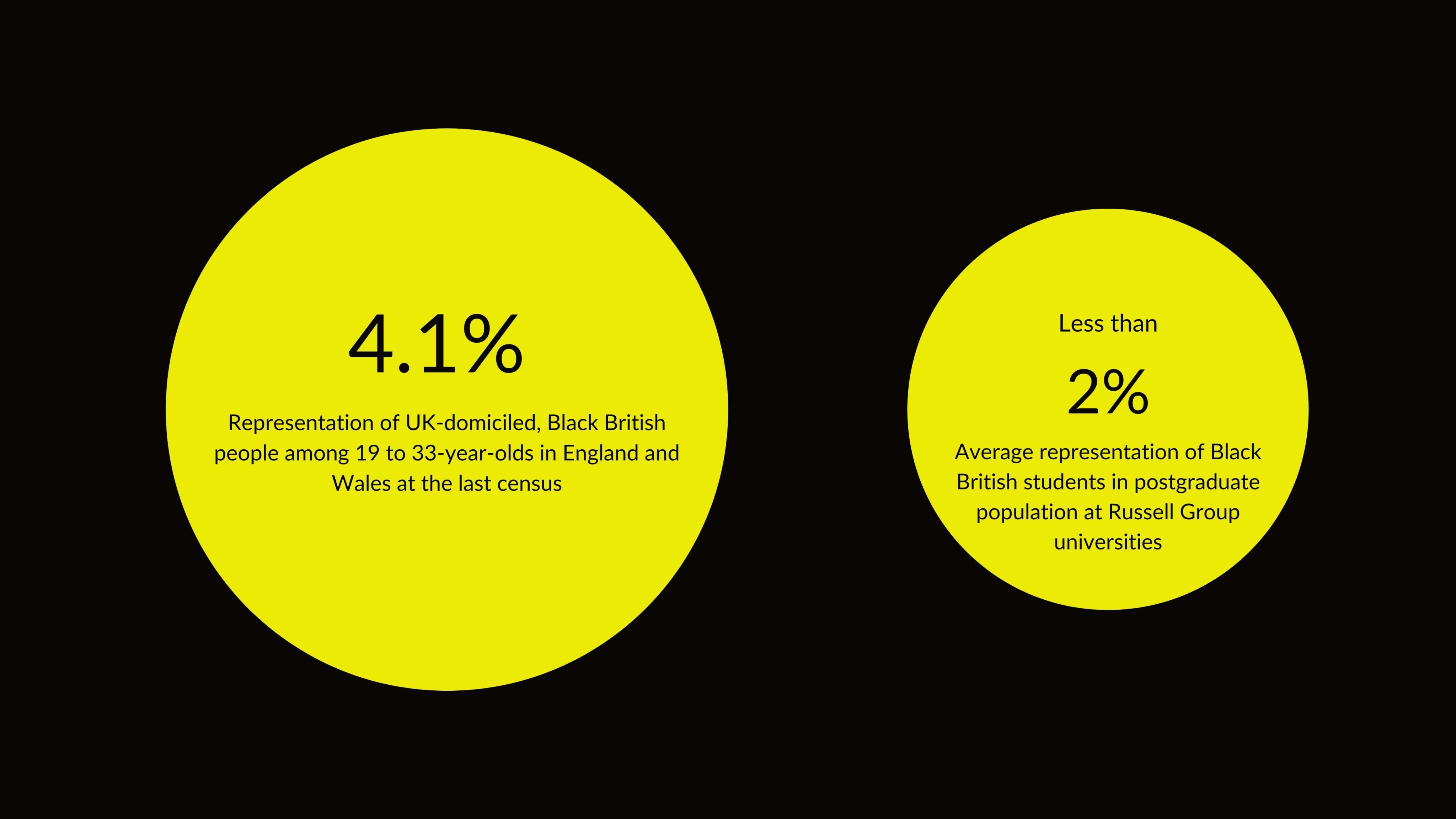

This is particularly the case among Black British, British Pakistani and British Bangladeshi students, on whom the new project will focus. For example, Black British people comprise about 4.1% of the population of 19 to 33-year-olds in England and Wales, but on average they comprise less than 2% of the postgraduate community at Russell Group universities. British Pakistani and Bangladeshi students are poorly represented in postgraduate education across the entire sector.

"If we want our universities to deliver the best research, we have to ensure that we are continually innovating to bring in the very best researchers, which means the system has to work for everyone."

Because fewer students from these backgrounds enter the ‘academic pipeline’, fewer then progress to academic careers. Like other universities, both Oxford and Cambridge have put considerable work into trying to improve representation throughout the system. Examples at Cambridge include the Experience PG and SHARE programmes, as well as the Black Advisory Hub.

Recent analysis has shown, however, that the challenge is not simply one of encouraging more students to apply. On average, Black British, British Bangladeshi and British Pakistani candidates are also statistically less likely to receive offers at many universities than their White counterparts.

This is the ‘offer gap’ that the new project will seek to address. The team will work with 16 departments (eight at each university). It aims to halve the gap in those departments by 2025, by making changes to their selection processes. Within one school generation – by 2035 – both universities intend to close the gap completely.

Dr Sara Baker, from the Faculty of Education and Cambridge’s academic lead, said: “This is a really exciting opportunity to drive forward real change for underrepresented groups in postgraduate study. If we want our universities to deliver the best research, we have to ensure that we are continually innovating to bring in the very best researchers, which means the system has to work for everyone.”

“Under-representation is a complex social issue, but this problem with acceptance rates is something we can control and should. What we want to know is, if the applications are there, what’s causing the discrepancies, and what could universities like ours be doing differently?”

Part of the offer gap may be to do with the previous academic experience of some groups of students. For example, those from under-represented groups often attend research-non-intensive universities at an earlier stage, and may be more at risk of being filtered out by admissions systems which put a strong emphasis on prior attainment, at the expense of evaluating potential.

Much remains unexplained, however, and the project will attempt to address this by mapping and analysing how postgraduate recruitment decisions are made within the participating departments. The team will analyse admissions data, and interview those affected and involved – including current postgraduates from these backgrounds.

The project will then test different, potential alternative approaches which take account of issues such as the different career trajectories often experienced by these students, how and when they apply, and what support structures are in place.

"We need that fresh thinking based on what has worked elsewhere – whether in the private sector, government, or other parts of society."

Prototype methods will be developed in consultation with project partners who have long experience implementing fair and race-literate recruitment models in other settings. They include Blueprint for All (formerly the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust), which aims to enable more young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to succeed in their career goals; and Rare, which supports racial equality and diversity in recruitment to elite companies and organisations.

The latter’s Contextual Recruitment System is one tool which could eventually be adapted for recruitment to postgraduate study and research. Other options may include the use of contextual ‘flags’ (indicating when a candidate comes from a marginalised background), or interview-all approaches. These interventions will only be decided upon, however, once the team has undertaken its initial research into the causes and drivers of the offer gap itself.

The prototypes will be tested over two to three doctoral admissions cycles. Across all the pilot departments and research clusters, it is estimated this will reach at least 1,000 and 1,500 applicants during the lifetime of the project alone. By its end, the team will have produced a clear set of recommendations and guidance about how the offer gap can be closed at Oxford, Cambridge, and other universities.

“The involvement of our partners is absolutely critical,” Baker added. “We need that fresh thinking based on what has worked elsewhere – whether in the private sector, government, or other parts of society. Universities are huge, complex, busy institutions; but we have to be open to taking stock and potentially challenging our own practices in this way.”

More information about the project is available on the University of Cambridge website.

Image in this story by University of Cambridge