How fairytales helped to break the gender binary in the playground

Gabrielle Spears is a former Primary PGCE and Masters student at the Faculty of Education. The research she undertook for her Masters thesis covered an innovative action research project in which she used fairytales to subvert traditional assumptions about gender in a particularly boisterous playground at the London primary school where she teaches. This work has since formed the basis of an article by Gabrielle which was published in an academic journal.

Here, she discusses how she came to study at the Faculty, the research project itself, and how it helped to change a group of children’s minds about what girls and boys ‘should do’.

I know it’s a cliché, but I’ve always loved working with children

I’m from Newcastle and moved to London in 2009 to read Ancient World Studies at UCL. I have always loved working with children, and after graduating, I worked in a school as a Teaching Assistant. That made me want to do a PGCE. I went for the interview at Cambridge, got a place and thought – yeah, I’m going for it. I did the Primary PGCE course at the Faculty back in 2014/15, then started teaching at a primary school in central London. I had always been interested in doing a Masters qualification, and returned to study for an MEd in Researching Practice in 2017/18. It’s a really exciting, open course, which allows you to research an aspect of your professional practice in depth.

Gabrielle Spears

Gabrielle Spears

My research study focused on a playground at my school, which had become a heavily gendered and sometimes frightening space

There are three playgrounds at the school and one – the Multi-use Games Area (or MUGA) – is a place that had been territorialised. Boys used it to play football and girls felt ostracised. It was quite a scary place for some children: there were balls flying everywhere, children getting hit, lots of slide tackles, lots of arguments and aggression. If girls tried to join in with the games, they were told that they were ‘too slow’. They were made to feel that the space was somehow off-limits.

I think it’s important that teachers challenge issues about gender identity as children grow up

The behaviour I saw in the playground wasn’t just reinforcing gender stereotypes there – it was coming out in the classroom as comments and asides. Boys repeatedly stressed that they were ‘stronger’ or ‘faster’, for example. The danger is that in the long run these stereotypes elevate some people over others. Playgrounds themselves are spaces where these ideas are worked out. Children start to develop a mental map of where they see themselves as welcome or unwelcome socially at a very young age, and of how they ought to behave. I wanted them to be able to empathise with each other, and to encourage a sense of social imagination and social justice.

Rather than give them a lecture on the subject, I decided to tap into their interests by using fairytales

I developed an intervention for the 30 Year 3 children whom I taught – 14 girls and 16 boys. The children love stories, and there is a lot of gendered language in traditional fairytales - I think that children learn a lot about gender through that medium. I wanted to explore whether I could subvert the traditional presentation of women as weak and vulnerable, and of men as strong and brave.

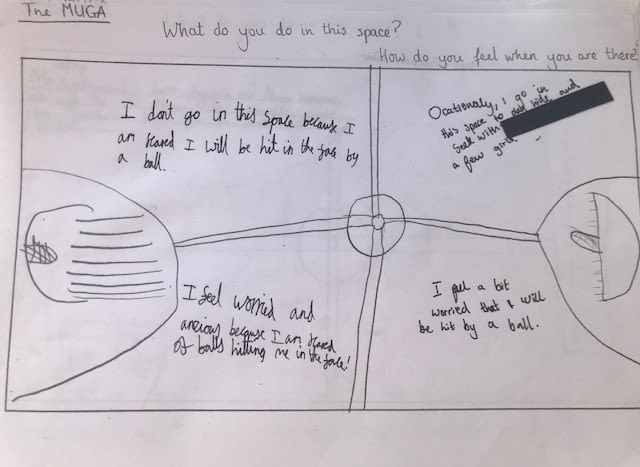

We started by mapping out the playground

I drew a rectangular outline representing the playground and got them to draw a map of the space and tell me how they felt when they were there. A lot of girls emphasised things like the court markings and a penalty shoot-out area. About a third of them mentioned feelings of anxiety about being hit by a ball. They described feeling fearful in that space. By contrast, the boys associated it with running around and having fun.

Map of the playground produced by children in Gabrielle's class

Map of the playground produced by children in Gabrielle's class

Next, we revisited an old fairy story – and read a new one

We then read a story that they had first been read in Year 1 – Snow White In New York by Fiona French. It’s a modern story, as the name suggests, but largely uses the traditional ‘formula’. I also read them The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch, which actively subverts traditional gender dynamics: it features a feisty princess who refuses to marry a prince and ends up saving him. I then distributed a questionnaire, with questions like ‘Which character stood out to you and why?’, and, ‘Which character would you like to be in the story and why?’

Finally, the children played out their own fairytale in the playground – with a twist

I wrote the start of a fairytale starring the children themselves – but in this version the boys had been captured by a dragon and the girls had to intervene and ‘save’ them. We re-enacted the story in the playground, and they improvised what happened next. Afterwards, I interviewed them separately about how being in that moment had made them feel.

The results from reading the two fairytales together showed how early children learn to be comfortable with their ‘expected’ gender roles

One girl told me that she wanted the princess and prince to marry in The Paper Bag Princess, for example, because ‘that’s a happy ending’. It took a bit of digging for them to think again and realise that the characters weren’t compatible, and that the princess didn’t have to marry the prince – maybe she could go and have a career instead!

The playground improvisation really changed the way they thought about that space

Most of the boys really got into the role – although one was very annoyed that he ‘could not destroy the dragon and had to wait for a princess’. The majority expressed relief at being ‘saved’ in our re-enactment, and didn’t comment on the role-reversal. The girls, on the other hand, all talked about how it felt good to be brave. It was a big deal for them – they have clearly grown up expecting male characters to exert their dominance over female characters and when they were able to play an active role in subverting this archaic expectation, their enjoyment was evident.

One really successful aspect was that I could see the boys acknowledging that they felt vulnerable in the improvised story. When I read the girls’ reflections to them, it helped to open up a conversation about what it might feel like to be vulnerable in that space every day. Four of the boys acknowledge that they could ‘slow down a bit’ to ‘make other people feel brave’ on the playground. Five suggested that they could invite girls into their games and sports.

We need to be mindful that playgrounds can be prescriptive spaces

As educators, we need to have an informed stance on challenging gender stereotypes, and to be careful about identifying situations where we can step in and challenge that. Mapping the playground out, and using it to test preconceived ideas about identity, played a big part in helping the children to understand that they should all be able to use those spaces to do what they enjoy, and not what they are traditionally ‘told’ to do.

The study also showed just how possible it is to have deep conversations with even young children about these issues

Remember the boy who showed anger at the role reversal? When we talked about how his feelings mirrored those that girls felt in the playground every day, he ended up vowing to ensure that ‘everyone has something to do and has friends to play with’ in the future. Something that surprised me was the level of maturity that 7 and 8-year-olds approached this with. I think we should be careful not to avoid those discussions with children – it’s made me think about how I can introduce ideas about gender equality into more of my lesson planning. The children love a debate – they’re really on board with it!

Gabrielle’s research can be read in the International Journal of Primary Elementary and Early Years Education.

Main image: Richard Webb, via Geograph.