Four priorities in inclusive education for the Global Disability Summit 2022

Four years after the inaugural event in 2018, the second Global Disability Summit is due to take place on 16 and 17 February.

These unique gatherings help to set the international agenda for improving the lives of people with disabilities. Crucially, the summits are led and determined by people with disabilities themselves, working alongside representatives of state governments, aid organisations, advocacy groups, research institutions, and private companies.

One of the main themes at GDS 2022 is ‘Inclusive Education’, which is the central focus of the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER): an international network of scholars and practitioners based at the Faculty of Education. The summaries below draw together evidence and findings that have emerged from some of CaNDER’s research since the last GDS four years ago. Together, they highlight four key issues that need to be addressed as we seek to make progress towards inclusive education globally in the years to come – and provide ideas and recommendations about how that might be achieved.

1: Inclusive education requires us to acknowledge the critical importance of school to the lives of children with disabilities.

Relevant CaNDER projects: Revisiting equity: COVID-19 and education of children with disabilities. (Research comprises projects across Ethiopia, Nepal and Qatar, and a separate COVID-19 project in Malawi).

Research in summary: All children have been affected by the pandemic, but the impact on those with disabilities has been particularly severe. In projects across Ethiopia, Nepal, Qatar and Malawi researchers interviewed parents, carers and teachers to find out both how COVID-19 had affected these children’s education and how their participation might be sustained.

Mwesigwa Joel (Unsplash)

Mwesigwa Joel (Unsplash)

These were not comparative studies, but some common themes emerged. Parents were frequently concerned about learning loss during school closures and the impact on their children’s prospects; many also felt keenly the loss of the care and socio-emotional support which pupils with disabilities often rely on schools to provide. Children lost their daily structure and contact with friends, and many parents noted that they seemed sadder, lonelier, or more anxious than normal. Many parents also expressed deep concern about the fact that they could not personally provide the specialised educational support their child needed at home; while some teachers felt inadequately equipped for the shift to remote learning.

At the same time, the research highlights the need not to generalise the experiences of children with disabilities. The surveys drew out some important differences both across countries and within certain sub-categories (notably when boys were compared with girls). In Ethiopia and Malawi, for example, teachers had far less contact with students during the pandemic than in Qatar. In Nepal, 23% of parents who had a daughter with a disability felt they could not leave their child alone during the working day, but only 7% of parents with a boy felt the same way.

Key recommendations:

- The specific needs of children with disabilities must be prioritised in national and regional COVID recovery plans. This means that data and research relating to the education recovery needs to take account of them as a distinct group, and provide clear information about the quality of education and support they are receiving.

- Strategies should be put in place to maintain the socio-emotional support that schools provide during any future closures.

- Teachers need to be given training to cover the full range of learner needs remotely, using low and high tech. Systems and schools should also ensure that remote learning resources and programmes are accessible to children with disabilities – for example, by supplying books in Braille.

- Stronger partnerships between schools and families need to be developed so that parents can be more actively involved in the learning of children with disabilities. This may, for example, involve providing basic training in skills such as sign language.

- Information about the education of children with disabilities needs to be disaggregated by both gender and background, to avoid one-size-fits-all solutions that will inevitably leave some vulnerable children behind.

Partners:

Ethiopia, Nepal and Qatar: Professor Nidhi Singal (Cambridge); Dr Shruti Taneja Johansson (University of Gothenburg); Dr Asmaa Al-Fadala (WISE); Aemiro Tadesse Mergia (University of South Africa); Dr Niraj Poudyal (Kathmandu University). Funded by: WISE, Qatar Foundation. Malawi: Jenipher Mbukwa-Ngwira (Catholic University of Malawi); Dr Shruti Taneja Johansson (University of Gothenburg); Dr Eric Umar (College of Medicine, Malawi); Dr Paul Lynch (University of Glasgow); Professor Nidhi Singal (University of Cambridge). Funded by: Cambridge-Africa ALBORADA Research Fund.

Find out more:

- Full report on the Ethiopia/Nepal/Qatar project and summary blog post.

- Research paper on the Malawi project and summary blog post.

2: Research and policy needs to draw more directly on the voices and experiences of persons with disabilities in the Global South.

Relevant CaNDER projects: Evidence on disability and education: the geo-politics of knowledge generation, evaluation and communication and Unpacking notions of disability and inclusive education in current African scholarship

Research in summary: In January 2020, researchers from CaNDER undertook a search of the Africa Education Research Database to explore how the education of children with disabilities in Africa is currently conceptualised, researched and understood.

By far the largest portion of the studies focused on primary education, rather than secondary and higher education or early childhood. Analysis of the primary-level studies then uncovered some significant gaps. Most focused on just a few countries, while a majority were not authored primarily by researchers in sub-Saharan Africa itself, but more often in North-South collaborations.

In addition, fewer than half of the research papers appeared to report studies in which children themselves had been involved as participants, while a large number failed to specify which disabilities were being studied, or the definition and model of ‘disability’ being applied.

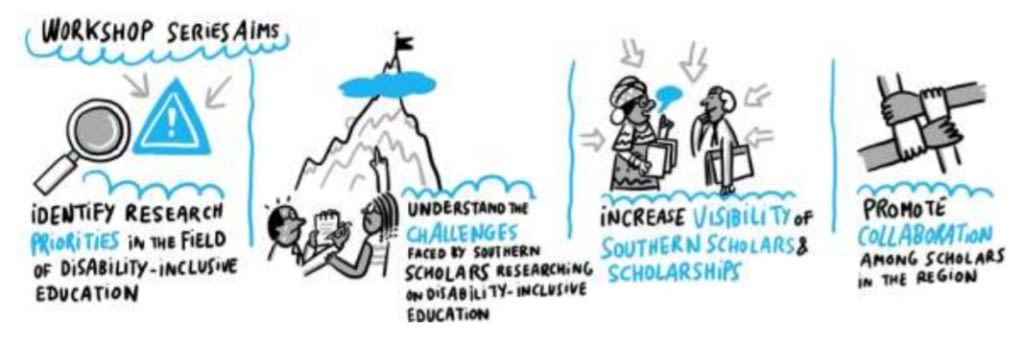

The findings raise important questions about whose voices ‘count’ in inclusive education research, and how to strengthen the involvement of a more diverse range of locally-based researchers from the Global South. This was explored further through workshops with researchers and academics from both Africa and South Asia, run by the Inclusive Education Initiative, and involving colleagues from CaNDER. These highlighted the challenges many of these researchers face, including obtaining funding, a lack of access to a robust research community, and time limitations due to wider professional commitments.

The workshops also echoed concerns raised by the African Research study that some stakeholders – pupils and parents in particular – are too often under-represented in research into inclusive education; and that such research often fails to take account of local barriers to education, partly because it is often defined by the Euro-centric lens of academics from the Global North.

Key recommendations:

- If research into inclusive education is to have meaningful results, then mechanisms need to be established to ensure that it is studied and assessed in context: relative to local circumstances, and mindful of the lived realities that shape the lives of children with disabilities in those settings. In particular, this means including the voices of children with disabilities in more research.

- A framework needs to be developed so that systems-level inclusive education policies are developed in dialogue with people throughout the system before they are implemented, so that the voices and concerns of practitioners, parents and people with disabilities are taken into account.

- Improving inclusive education in a manner that addresses learners’ own contexts is likely to involve identifying and adopting local strategies to promote it. This may, for example, involve forming school inclusion committees, or starting local fundraising campaigns to make certain improvements.

- New fora and opportunities should be created so that researchers in the Global South can collaborate in South-South partnerships. Some online communities are already being created through the Inclusive Education Initiative.

Partners:

Professor Nidhi Singal, Carrie Spencer (University of Cambridge); Dr Rafael Mitchell (University of Bristol) and for the workshop series: Inclusive Education Initiative, University of Gondar and Kathmandu University.

Find out more:

- Video Presentation: Primary schooling for children with disabilities - a review of African scholarship

- Final report from the Inclusive Education Initiative (World Bank) Research Exchange Workshop Series

3: Steps must be taken to promote, build and support a truly inclusive education workforce.

Relevant CaNDER projects: The work lives of disabled teachers in England: levers for change; Promoting an inclusive education workforce: perspectives and experiences of teachers with Disabilities.

Research in summary: Around the world there have been various commitments to ensuring a more diverse teaching workforce, but surprisingly little attention is paid to those with disabilities. In one of the first academic studies examining the working lives of these teachers in England, CaNDER researchers similarly found that many teachers with disabilities encounter “significant discrimination and barriers” at work. This rarely reflects the prejudice of colleagues, but rather the pressure placed on various schools by performance targets which make it difficult for them to accommodate a diverse workforce.

14995841 from Pixabay

14995841 from Pixabay

Many teachers with disabilities feel lonely or undervalued as a result, while some described “poor disability awareness” and even “a hostile environment” when they tried to ask for reasonable changes. At the same time, the study highlights that teachers with disabilities are a huge asset to the workforce: they tend to be highly empathetic and skilled at differentiating their teaching and learning methods to suit different students. By definition, they help to make schools more inclusive places that promote positive attitudes towards people with disabilities.

Such findings seem to be echoed internationally, according to an exploratory project which provided a snapshot of the experiences of English language teachers with disabilities in Nepal, India, Rwanda and South Africa. Teachers in all four settings were very conscious that they were role-models within schools who can also bring important soft skills, such as empathy, to the school environment.

These teachers also cited barriers in their working lives that included transport difficulties, fatigue, increased workloads during the COVID-19 pandemic, and in some cases social stigma. Not all of the teachers interviewed had managed to have reasonable adjustments made to accommodate such needs at the schools where they worked.

Key recommendations:

- More people with disabilities need to be recruited into education systems. For schools this tends to represent a ‘double-win’, as they make schools more inclusive places, while bringing important qualities into the school environment.

- Teachers with disabilities need to be an active part of the discussion on making education more inclusive; acknowledging their voices also avoids strategies in which they are treated as ‘objects of pity’.

- Many teachers with disabilities told researchers that they would benefit from networks which allow them to share experiences and skills with others who are in a similar position. Efforts should be made to create an ‘international community of practice’ to that end.

- Teachers – and especially school leaders – should receive training on inclusive practice towards colleagues, and on disability rights.

- More data needs to be made available on the experiences of teachers with disabilities to inform policy and practice, and prevent their frequent marginalisation in education systems.

Partners:

Dr Hannah Ware, Professor Nidhi Singal (University of Cambridge); Professor Nora Groce (UCL). Funded by: University of Cambridge / British Council.

Find out more:

- Research article: The work lives of disabled teachers: revisiting inclusive education in English schools.

- Animation of findings.

- Report for British Council: English language teachers with disabilities: an exploratory study across four countries.

4: EdTech must support children with disabilities both to learn and to have agency in their learning

Relevant CaNDER project: EdTech and education of children with disabilities.

Research in summary: This study set out to understand how EdTech can support children with disabilities aged six to 12 in lower-income countries. The team reviewed existing evaluation and trial reports which assessed Educational Technologies designed for this purpose.

EdTech is widely seen as having the potential to level the playing field for these children by improving their access to, and engagement within, education. The study, however, found an ‘astonishing’ shortage of evidence about which innovations are best-positioned to help which children with disabilities in lower-income parts of the world. Just 51 relevant reports were identified in a survey which screened 20,000 documents produced between 2007 and 2020.

Large parts of the world – for example, most of South America – were barely represented; many of the trials reported were short and involved small sample sizes; and there was a deficit of studies evaluating technology for certain types of disability, particularly physical disabilities. In addition, most of the existing literature reported tests of whether children found the technology easy to use, without assessing the difference it made for their learning outcomes. Few studies assessed teachers’ knowledge, attitude and skills when using the technology. Similarly scant attention was given to the views of parents and carers.

Despite the general shortage of evidence, the study uncovered some information about how portable devices in particular are transforming opportunities for children with disabilities. For instance, the research provides examples of how deaf and hard-of-hearing pupils are increasingly using SMS and social media to access information about lessons.

Key recommendations:

- There is a clear need to ensure future research on EdTech is more systematically aligned to the aims for inclusive education stated in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. This means ensuring that assessments look beyond the question of access, and at whether EdTech is providing children with disabilities with quality learning experiences.

- To strengthen accountability, clear national guidelines are needed regarding who is responsible for sourcing EdTech for disabled learners.

- Governments should invest more in technology – for example, mobiles and portable devices – which has been shown to improve ubiquitous learning opportunities in schools, residential settings and homes.

- Research into EdTech for children with disabilities needs to be widened out so that involves more users: taking account of teachers, parents, carers and, of course, the pupils themselves.

Partners:

Dr Paul Lynch (University of Glasgow); Dr Gill Francis (University of York), Professor Nidhi Singal (University of Cambridge). Funded by: EdTech Hub.

Find out more:

- Research paper: EdTech for Learners with Disabilities in Primary School Settings in LMICS.

- Summary blog post.

- Policy recommendations.

Additional credits for images used in this article:

“Deaf School Sri Lanka”, by Izhorsky, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 / Students learning at school, Ludi via Pixabay