Not just about headteachers: getting to grips with leadership and learning

Leading and learning are often mentioned in the same breath – but when we talk about ‘leadership’ in education, what (and who) do we mean? In January, the University of Cambridge will be running a course for current professionals on ‘Leadership for Learning with Dialogue’. Drawing on decades of international research on the subject, its aim is to equip teachers and other practitioners with a working knowledge of what it means to ‘lead’ for learning – and how this can enable meaningful and positive changes in schools, universities and beyond.

Leadership has rarely been a hotter topic in society than it is right now, and for as long as it has dominated our politics, it has also been connected to education. Educators in the past, like some today, frequently spoke of cultivating the ‘leaders’ of tomorrow. Education policy is replete with references to school leaders, senior leaders, leadership teams, and project ‘leads’.

But what does any of this really mean? All of these terms seem to imagine leadership as something done by individuals, or, at most, a small group of them. There is, however, a different way of looking at leadership in education, and that is as a shared endeavour that students, staff and entire schools undertake together.

This rather different conception lies at the heart of a new, three-month course in Leadership for Learning with dialogue, which the University of Cambridge will be running for professionals, both inside and outside education, who want to develop their capacity to lead change where they work. The course, which starts in January 2023, is part of the ‘Transforming Practice’ Practitioner Professional Development programme at the Faculty of Education.

Its starting point is a body of scholarship that suggests meaningful change in our schools, universities, or other organisations requires us to think deeply about what leadership in support of learning actually looks like. Over the past 20 years, a network of researchers based at Cambridge have developed and refined a tool to help professionals address this, known as the Leadership for Learning Framework.

A central component of both the framework and the new course is the role of dialogue – the act of sharing, challenging and refining ideas. It is closely linked to a more fundamental belief that we need to challenge leadership as the work of ‘heroic’ individuals. As Professor John MacBeath, the original director of the work at Cambridge put it at the time: “Leadership does not just rest with the headteacher; it should be exercised at every level within a school and its community.”

What is Leadership for Learning?

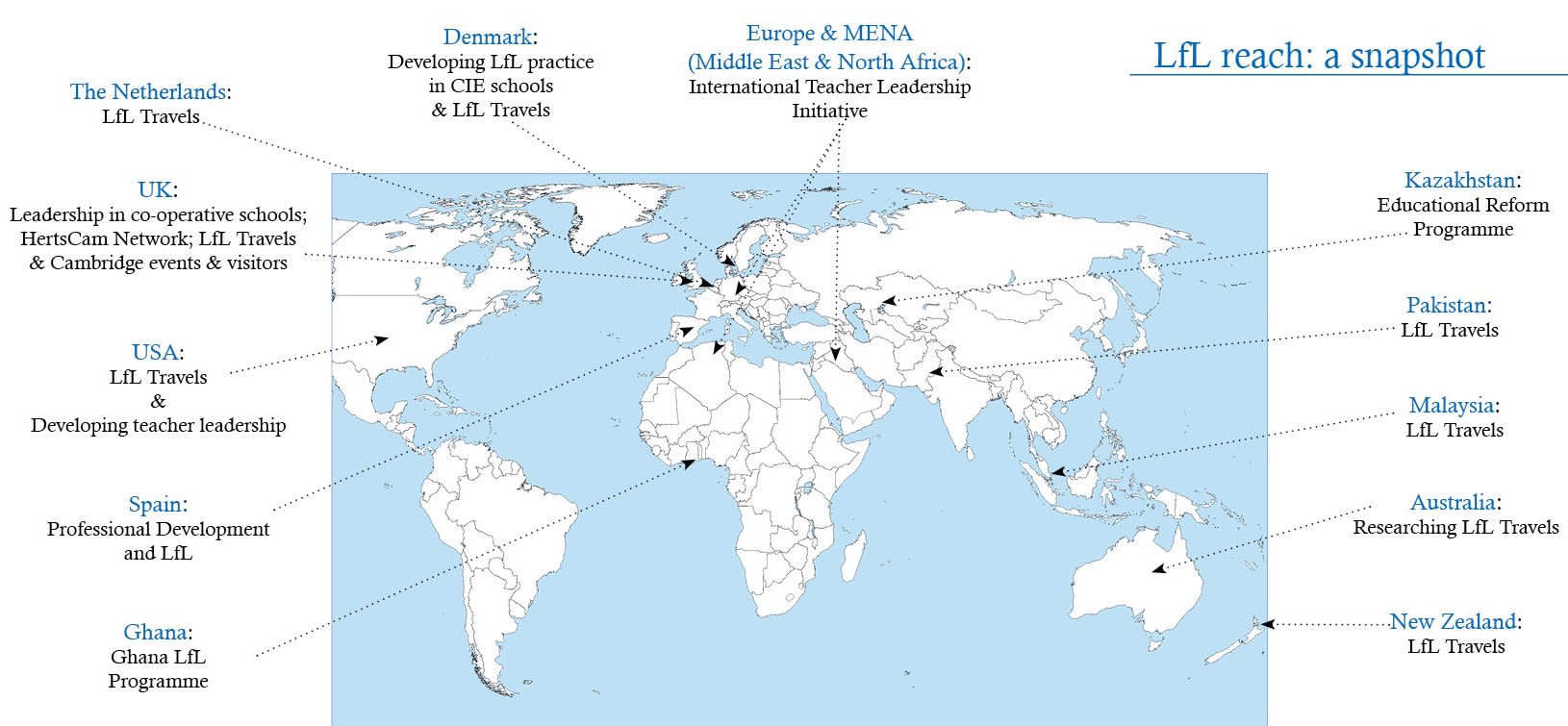

The original Leadership for Learning research project was set up back in 2001 to study how these deceptively simple terms interrelate. The researchers and practitioners involved came from seven countries and, over four years, worked with a network of schools, to try to understand what effective leadership looks like in education.

Specifically, the team wanted to understand the connections between leadership and learning, illuminating how we can most effectively lead learning and what practical strategies will help. What eventually emerged was the ‘Leadership for Learning’ (LfL) framework to which students on the new course will be introduced.

Several important ideas underpin this. One is that both leadership and learning should be seen as activities as well as roles. Leadership, for example, involves influencing others, taking initiative, modelling behaviours, and making choices that benefit others. Learning involves posing questions, analysing things, and testing ideas. Neither is therefore just about what we do alone, they also concern what we do together – and a unifying sense of purpose is therefore key.

Dr Sue Swaffield Associate Professor in Educational Leadership and School Improvement at the Faculty of Education, who will be leading the course, has highlighted the importance of ‘agency’: ensuring that everyone involved in a process feels empowered to enact what may often be small, but significant, expressions of leadership. “We have all had that experience of thinking ‘I wish I had said this, or done that’, when it was too late,” she reflects. “Those are often moments when, even if only briefly, we might have provided some form of leadership. When we talk about agency in Leadership for Learning, we partly mean how we can equip people to seize those moments – how to make them feel like they can speak up and make a difference.”

Dialogue and the LfL framework

The LfL framework identifies five principles that, together, characterise effective leadership for learning. These are:

1. Maintaining a focus on learning as an activity; particularly one in which everyone – students, teachers, the school itself – is learning.

2. Creating conditions that are favourable to learning as an activity; for example, by cultivating an environment where everyone can take risks, cope with failure and respond positively to challenges.

3. Creating a dialogue about Leadership for Learning, so that the very practice of leadership is explicit and discussed.

4. Sharing leadership, for example, by ensuring that everyone is encouraged to lead on aspects of the initiative in question.

5. A shared sense of accountability: for example, by making sure that the project takes a systematic approach to evaluation.

The new course will provide an overview of the full framework as well as introducing the work of Paulo Freire – an example of the international scholarship to which the framework is closely related. It will, in particular, emphasise dialogue – and the closely associated question of a democratic approach.

Imagine, for example, that a teacher is charged with overseeing something fairly simple – like a new waste recycling initiative in a school. This is not something they are likely to be able to ‘lead’ alone. For the new system to work students will need to exert their own leadership in positive ways, perhaps by placing their lunch packaging in the correct bins and encouraging their peers to do the same.

Dialogue is critical to this idea of shared leadership, because it is about how we create meaning and develop a collective understanding of what we are seeking to achieve. In addition, projects such as this will only tend to work when leadership and responsibility are openly discussed and shared among those involved. Those same people also need to be in effective dialogue to swap ideas and concerns about the project as it evolves.

Perhaps most fascinatingly, dialogue is not always explicit or stated. Specialists in dialogue point to the fact that in any classroom or group, tacit forms of knowledge and understanding, such as assumptions, are also flowing between people. Enabling that flow, and understanding how and why it might be impeded, is critical to shaping positive changes in any setting.

Leadership for Learning in practice

Since its conception, the LfL framework has been used to shape many projects around the world. Its success seems to be attributable to its ability to push beyond the idea of training individual ‘leaders’ and to articulate a more profound sense of what it means to lead in education. “The framework provides a sort of common language for thinking about leadership and learning,” Swaffield says.

As a result, the LfL framework has been shown to be useful to practitioners at any stage of their career. It is also applicable to almost any situation where an education professional needs to lead a process that is meant to enhance learning.

For example, the framework has informed initiatives to support student revision, to involve parents in the life and work of their children’s school, to set up departmental reading groups, and to instigate whole-school approaches to professional development. One school has used it to establish a new team of teachers focused on building student-centred approaches to learning. Another drew on LfL to develop a programme which encouraged students to think about their careers and possible futures earlier than normal in their education and then used this as the basis of developing new learning opportunities.

Alongside learning about the Leadership for Learning framework the course has a parallel focus on small scale enquiry including critical reading and writing. Students on the new Transforming Practice course will be enabled to use the framework to plan, conduct and evaluate a small-scale enquiry-based intervention of their own. They will be helped to gather and analyse data, communicate effectively and activate ‘critical friendships’ as they put their intervention into practice.

“Leadership is something that is in everyone’s hands,” Swaffield adds. “Educators can draw on these principles to make a difference every day, to their students, their colleagues, and their school. At every level, dialogue is critical to how we do it.”

Leadership for Learning with dialogue runs from January to March 2023. Further details are available on the Faculty of Education website. The deadline for application is 1 November, 2022.

Images in this story: Faculty of Education / LfL network