Profile:

Rosemarie Frost

Maths teacher and "compulsive learner" who took the part-time Cambridge MEd. in Mathematics Education to understand more about her students' perspectives on learning

Rosemarie Frost has been teaching secondary school maths for more than 35 years and, as a self-confessed ‘compulsive learner’, has continually supplemented that professional experience with a variety of academic and professional development courses. In 2020/21, she completed a part-time Masters course in Maths Education with the Faculty. Here, she explains why she chose the course, what the experience was like, and how it helped her to challenge and refine some of her ideas about what works in mathematics education.

I’m a bit older than your average MEd student

In fact, it won’t actually be that long until I retire! I originally studied for a BEd at Dundee University, which got me started teaching mathematics. I worked for a number of years at St Albans Girls’ School, which is quite a large comprehensive school, where I was very happy. Later on, I decided to get a proper Maths degree, which I did with the Open University, and that enabled me to become Head of Department at an independent girls’ school – St Albans High School for Girls – where I work today. I’ve been here for 25 years and am now Senior Teacher, which is similar in some ways to being an Assistant Head.

"I thought it might help my career but in the main I’ve just always been keen to take opportunities to learn more"

I’ve always been a bit of a compulsive learner

Not long after I started at my present school I decided to get some extra qualifications. In part, I thought it might help my career but in the main I’ve just always been keen to take opportunities to learn more. It started with a part-time MA in Education, again with the OU, in the late 1990s, but more recently I’ve completed various courses at Cambridge.

The first was an assessment and examinations course which taught me a lot. As a teacher, if you’re not told otherwise, you tend to assume that ‘assessment’ is just writing a test and marking it. The course showed us why what matters is not just the process, but the inferences you draw from it. For instance, an A-Level Maths exam is valid when it comes to assessing a candidate’s knowledge, but is it really a valid basis on which we should be structuring league tables? I’ve since encouraged that deeper understanding of assessment where I work. It applies at a granular level as much as for tests. Even if you’re doing something as simple as asking your class a question, it helps to be able to reflect on why you’re asking it and what inferences you hope to draw from the answers.

Although I had done a Masters before, the Maths Education course was a complete eye-opener

I followed up my assessment course with one in research methods. This effectively put me on the road to getting my MEd, so I thought I might as well finish it! At a personal level, and not having had the opportunity to go somewhere like Cambridge when I was younger, I think part of me just wanted to show that I could do it.

The experience was completely different to anything I had done before and really introduced me to what makes the Faculty different. As I constantly tell my own students, Cambridge is all about high-level research. If you come here, you’re entering that world, but you will also be guided through the experience by the close personal support for which the university is well-known.

The initial stages of the course were really helpful both in introducing us to research methods, and getting us to think about our own research project. There were really interesting lectures that helped us to get into that headspace and my supervisor, Steve Watson, was a great help in understanding how you actually do proper research.

My research question emerged from an interest in the limits and possibilities of Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) has been a big buzzword in education for a while. In essence, it’s an approach to learning based on the fact that our working memory only has so much capacity to handle new information at any given time.

When it first emerged, I got quite excited about it: in some ways CLT confirmed things I had been doing for years. Having followed the approach closely in the classroom, however, to be honest, it didn’t always seem to make much difference to what my students learned. I began to realise that, of course, it’s not just what the teacher does that matters, but what students do as well – and that the environment they are in and what they themselves bring to the classroom makes a difference. For my dissertation, I decided to explore students’ perspectives on learning mathematics to understand more about this.

The findings show just how important cultivating the right classroom environment is to teaching maths successfully

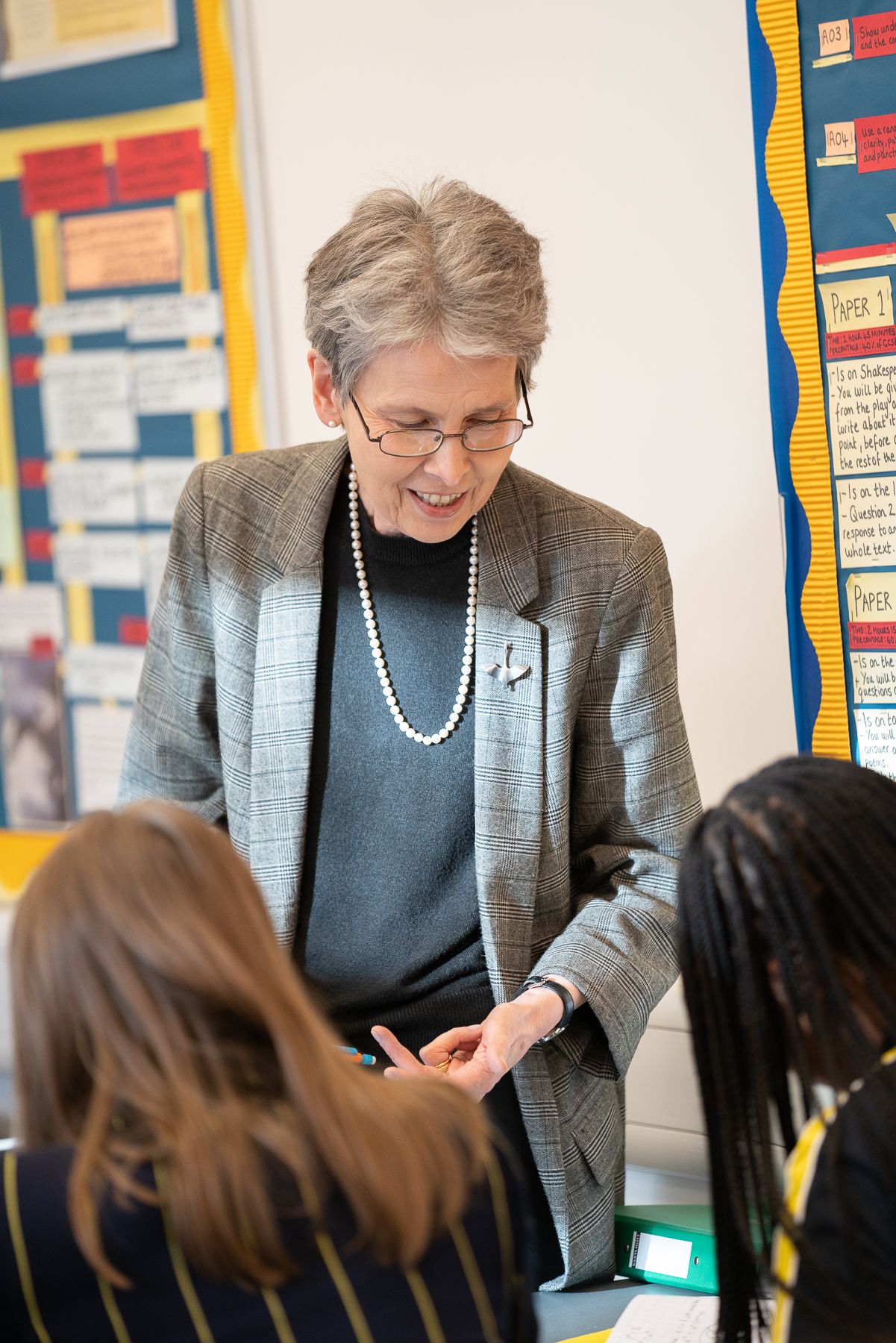

The research was a case study with my Year 11 group, who generally found maths hard. I asked them to write two stories, of which one, called “Me and My Maths Classroom”, really opened a window on to their experience as learners.

By ‘classroom environment’ I mean what the classroom is like, what the teacher is like, and how they and the students interact. These characteristics play a significant role in shaping pupils’ experiences of maths education. I discovered that, whilst my Year 11s may not have loved maths itself, they loved learning maths together. To my surprise, one of the things that had helped was a non-negotiable seating plan that I changed every term. Having sat next to different people, rather than just their friends, they all grew to like each other and that helped to create a mutually supportive atmosphere in the classroom.

I found that encouraging collaboration was key. For example, if one pupil was grappling with a question, I would ask another pupil whom I had already helped with the same problem to help them. That sense of being given ownership of their own learning was something to which they responded well. Another important insight was how much they valued the classroom being a safe space where it was alright to be wrong. A number of them wrote things like: “I like coming into this classroom: I know that nobody will make judgements about me and I can ask questions if I don’t understand something.”

"The MEd opened my eyes to what makes my students tick"

The MEd was a journey into research, but also a journey into the world of my own students

It was exciting to learn how research operates, how you present it, what a case study really is. You learn a huge amount and it was rewarding to feel part of a much bigger research community.

Perhaps more importantly, the MEd opened my eyes to what makes my students tick. I’m now very interested in the importance of consulting students. Most of us in teaching think that we’re doing this when we ask them how they are, but very few of us really investigate what being in our lessons is like for them.

I’m now applying what I learned with new classes: getting them to work together, giving them ownership of the learning process, and constantly, constantly reassuring them that it’s alright to make mistakes. I still use CLT, but I no longer expect it to be a magic bullet that will ensure all students get the top grade. I also came away from the MEd realising we should look at more than grades alone. What about that love of learning we are supposed to instil in our pupils? What can we do to make sure that whatever their GCSE scores, pupils develop an enthusiasm for maths and realise that it’s something they really can enjoy learning together?

They always say that you don’t regret what you have done – only what you haven’t. I passed my MEd with merit and looking back on it now, a year later, I think, ‘Gosh, did I really do all that?’ I learned and developed on that course far more than I ever thought I could. In the end, it’s changed the way I understand myself, as a learner, a researcher, and as a teacher.