“Tink” outside the box

The outcomes of a pan-European project which trialled the hands-on learning approach known as ‘Tinkering’ show that it could be used to develop the STEM skills of adults who are underserved and underrepresented in those subjects.

A project which explored the potential of the informal learning style called ‘Tinkering’ for adult learners has shown it could help STEM learning organisations better engage with and learn from underrepresented adults, especially with Europe’s more marginalised communities.

The pan-European trial covered five countries and tested the viability of Tinkering as a way of supporting lifelong learning in the ‘STEM’ disciplines: science, technology, engineering and maths.

It was part of the wider Tinkering-EU project, which is investigating the possibilities of Tinkering: an experiment-based, open-ended style of science education, often characterised as “thinking with your hands”. While there is evidence that this can support young people’s engagement with STEM, whether it works for adults has not been fully explored.

Several international surveys have raised concerns that many adults across Europe lack scientific literacy, skills and opportunities to explore new ideas in STEM. There is a particular risk that among socially marginalised groups – such as those with disabilities, or ethnic minorities – this deficit could lead to weaker job prospects and greater exclusion.

Through the Tinkering-EU project, 600 learners – among them refugees, prisoners and unemployed young adults – co-designed and participated in Tinkering workshops over the course of two years. The activities included tasks like building furniture from recycled cardboard, creating electronic greetings cards, and dismantling old toys to create new devices.

The reflections of the project partners, who were science centres or organisations which specialise in increasing public engagement with science, are documented in a newly-published report co-authored by academics at the University of Cambridge and the participating practitioners.

Emily Harris, from the Faculty of Education at Cambridge, who co-authored the report, said: “One of the most gratifying outcomes was that it supported deep relationship-building between science centres and local communities who are underrepresented in these spaces. Hopefully their reflections will provide other science engagement professionals with ideas and inspiration about how Tinkering could support the development of more inclusive adult STEM learning programmes, and about how they might adjust their own practices from deficit models to assets -based approaches which deeply value the experiences, skills and perspectives adult learners bring’.

Below is a summary of some of the main points raised by the report, Tinkering EU: Addressing the Adults, which can be downloaded from the project website.

About the project

Tinkering-EU has run several projects exploring Tinkering’s potential in STEM education. Unlike formal learning methods, Tinkering asks learners to try things out for themselves as they work towards a goal, for which there is rarely one right answer. In a typical exercise, participants are presented with tools or materials and asked to complete a task such as making a machine that can move or constructing a circuit. How they achieve that is up to them, with ideas developing as they start to engage in the activity.

The partners for the most recent project were science education and engagement centres in Austria, France, Italy the Netherlands and Poland. Each collaborated with at least one community organisation which works with a specific group of adults who may feel that science is ‘not for them’ or who generally do not participate in STEM activities. The participants included immigrants and refugees, out-of-work young adults and inmates at a prison.

The activities varied widely. One workshop, for example, asked participants to create art that conveyed a message – such as a warning or political idea – using a micro:bit computer and some basic coding. Another ‘upcycled’ old cardboard items to create usable furniture such as nightstands, chairs and shelves. Some others involved taking apart electronic toys to make new devices, growing ‘mini-gardens’ for the home, or weaving together materials with different properties.

Did it work?

All the partners felt the approach showed promise in several ways. Many found that by collaborating with community organisations, they reached adults who might otherwise never have visited their centre or museum, despite often living nearby. The team at the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw, for example, welcomed the opportunity to work with people “who do not already know or visit us”, while the National Museum of Science and Technology in Milan saw an opportunity to broaden their appeal beyond “the middle class, tourists and school groups.”

Overall, Tinkering did seem to engage the participants. For example, the team from TRACES – a French non-profit specialising in the public communication of science – noted that: “It gave a space for exploration and expression. It was not an activity where we, as facilitators, had to say a lot and they had to listen. The participants had time and space to express themselves. This brought engagement and energy.”

All of the partners are also aiming to maintain their relationship with the community organisations they collaborated with, and to run future Tinkering workshops for adults as well as children.

Lessons learned

Running effective Tinkering workshops with adults was not always straightforward. Three big themes emerged from the partners’ reflections.

1. Co-create wherever possible

There are plenty of standard Tinkering activities for younger audiences. Some of these translated very well for adult learners but others did not automatically work. Science engagement teams looking to take this approach in adult education need – as one team put it – to ‘tinker with Tinkering’.

Involving the community organisations closely in the planning process was key. The team at the NEMO Science Museum in Amsterdam, for instance, found that: “You need to take time to build a connection so that [the participants] understand what you want and you understand what they want”. Similarly, ScienceCenter-Network in Austria found their collaborating organisations crucial in helping them to “unlearn doing things the way we normally do them”.

Community groups generally provided crucial insights into how to make the activities effective.

For example, the Polish team worked with the ‘In the mother’s heart’ foundation, which helps people with disabilities and those struggling with their finances to develop new skills. They consulted with their participants on themes and topics of interest to help co-develop new tinkering activities. This highlighted their participants’ interest in interior design, home decorating, arts and crafts and gardening – which led to the development of an activity that ‘upcycled’ old cardboard as furniture, and another in which they created mini-gardens for inside their home.

2. Cultivate allies

All five partners realised that top-down approaches when working with marginalised communities create barriers to participation and may make Tinkering ineffective.

The participants themselves sometimes played an important mediating role to prevent this from happening. ScienceCenter-Network in Vienna, for example, ran sessions with refugee women and young adults on dyeing fabrics and creating illuminated gift cards using simple electronics.

Some ended up becoming ‘co-facilitators’. “They became a link between us and the participants – they were a bridge,” the team noted. At least one is still volunteering with the group and helping to run other activities.

TRACES, in France, ran a Tinkering session with male inmates serving long-term prison sentences, with whom it can be particularly difficult to build trust. Their collaborating organisation – the SPIP training service – already had an established relationship with the prisoners.

The involvement of this partner not only as a consultant, but as a facilitator, was critical to the success of the activity, which involved designing and creating sound-making devices.

3. Make it meaningful

Many Tinkering activities started to work, in particular, once the participants felt what they were doing mattered, or was personally meaningful.

The fabric-dyeing activity in Vienna, for example, invited participants to experiment with different techniques such as shibori, batik and tie-dye, while also introducing them to concepts such as pH levels and colour theory.

The ScienceCenter-Network team found that it worked particularly well because the participants could wear or share the dyed clothes and fabrics they produced. In addition, many of the immigrant women involved had experience of dyeing techniques they could teach others. The value of meaningful outcomes, and of giving participants the opportunity to inject something of their own culture, experiences and stories into the work, was noted by partners in all five countries.

Time for a re-tink?

The project partners intend to maintain their relationship with the community organisations involved, and/or to expand their Tinkering work to include older age groups. The initiative has made them reconsider how they might work with communities of adults whom they had previously thought it impossible to reach.

The Copernicus Science Centre team, for example, reflect in the report that their existing Tinkering activities “perhaps focus too much on kids and teens”. The team from the science and technology museum in Milan, similarly, observe that “Tinkering could, in the long run, help shape a new image of the museum. Rather than being perceived as a place only for the few, it could become a place of belonging for all, encouraging them into just ‘being’ and engaging with science.”

It is likely that more needs to be done to build wider recognition of the potential public value of Tinkering to enable this. The TRACES team, for example, acknowledge its “huge potential” for lifelong learning, “particularly in prisons”. They add, however, that “Public funding bodies do not yet understand the value of Tinkering as a pedagogy for adult learners. The notion of ‘exploratory space’ is not well-known or understood. But at some point, we know we will make this work.”

Growing beyond STEM?

The authors of the report also suggest that, beyond STEM education specifically, Tinkering is, to some extent, an ‘attitude’ that could characterise a much wider range of learning experiences.

Mark Winterbottom, Professor of Science Education at the University of Cambridge, said: “We know the value of open-ended, exploratory learning, for engaging young learners in science. In this project, we saw that value for adults, but we also saw how the project helped our partners to reflect on their practice more widely, with a view to generating more inclusive programming. Understanding the value of listening to learners, and giving them ownership and autonomy in their learning, is essential to successful engagement, whether in formal or informal spaces, and whether learning about STEM or something else entirely.”

Images in this story (top to bottom):

Immigrant women participating in a Tinkering session on ‘interweaving’ different materials at the Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan, as part of the Tinkering-EU initiative.

Detail from interweaving workshop.

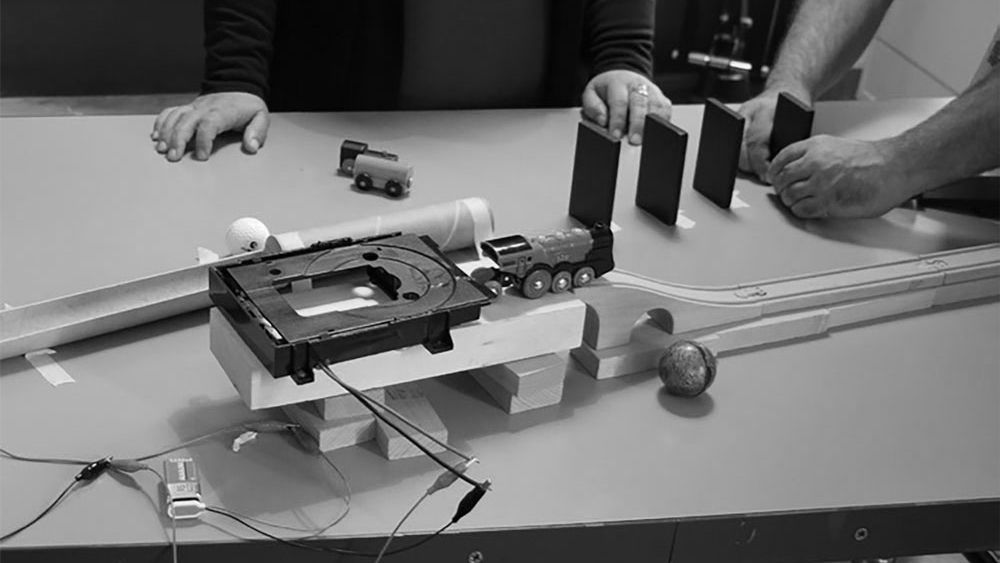

Chain reaction activity, run by Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan.

Dismantling and merging electronic toys, run by TRACES, France

Making 'Wishcards'. ScienceCenter-Netzwerk.

Making mini-gardens. Copernicus science centre, Poland.

Learners at the interweaving workshop, Milan.

Cardboard furniture. Copernicus science centre, Poland.

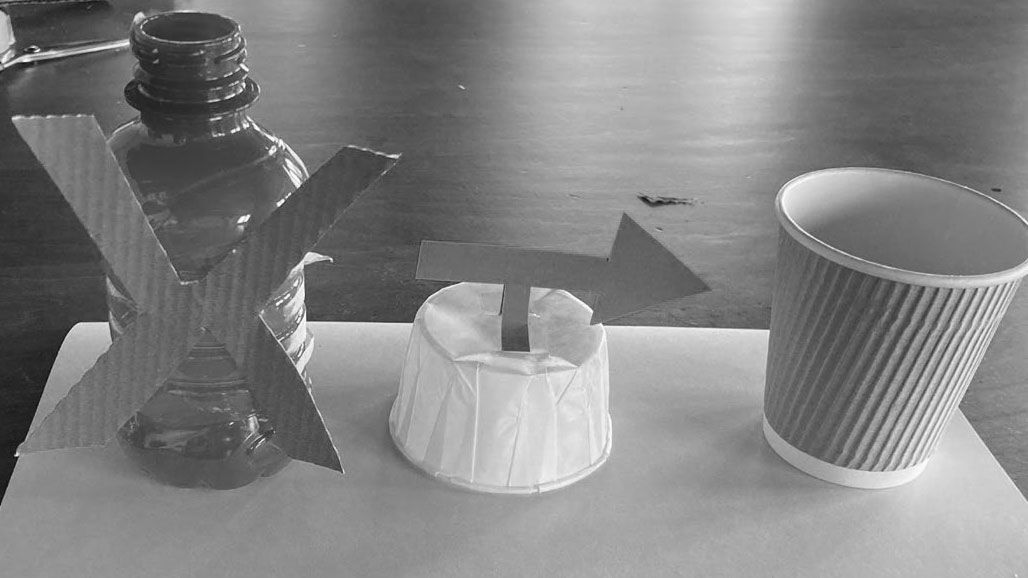

"No to plastic yes to paper cups": One of the outcomes of the 'making a message with art' activity run by the NEMO science museum.