New edition of leading Latin course more accurately depicts roles of women, minorities and enslaved people in the Roman world

The Cambridge Latin Course has been a mainstay of Latin learning in British schools since the 1970s. The new fifth edition represents one of the most significant new editions in its 50-year history. Alongside other aims, it addresses concerns raised by teachers, academics and students about the representation of women, enslaved people, and minorities in the Roman world.

Breaking news from 79 CE: Caecilius has a daughter. Barbillus is a Greco-Syrian man of colour. Enslaved people aren’t always happy. Metella is reading in the atrium.

These statements may read like indecipherable babble to some, but for students of Latin, they are among the most notable changes in the new edition of the Cambridge Latin Course: the leading textbook in the ancient language.

The course, a mainstay of Latin learning in British schools since the 1970s, has something nearing cult status with its fans. Its vivid stories, beginning in Book One with the adventures of a Pompeiian family featuring Caecilius, his wife, Metella, son, Quintus, and cook, Grumio, have inspired fan fiction, artistic tributes and even a cameo on Doctor Who.

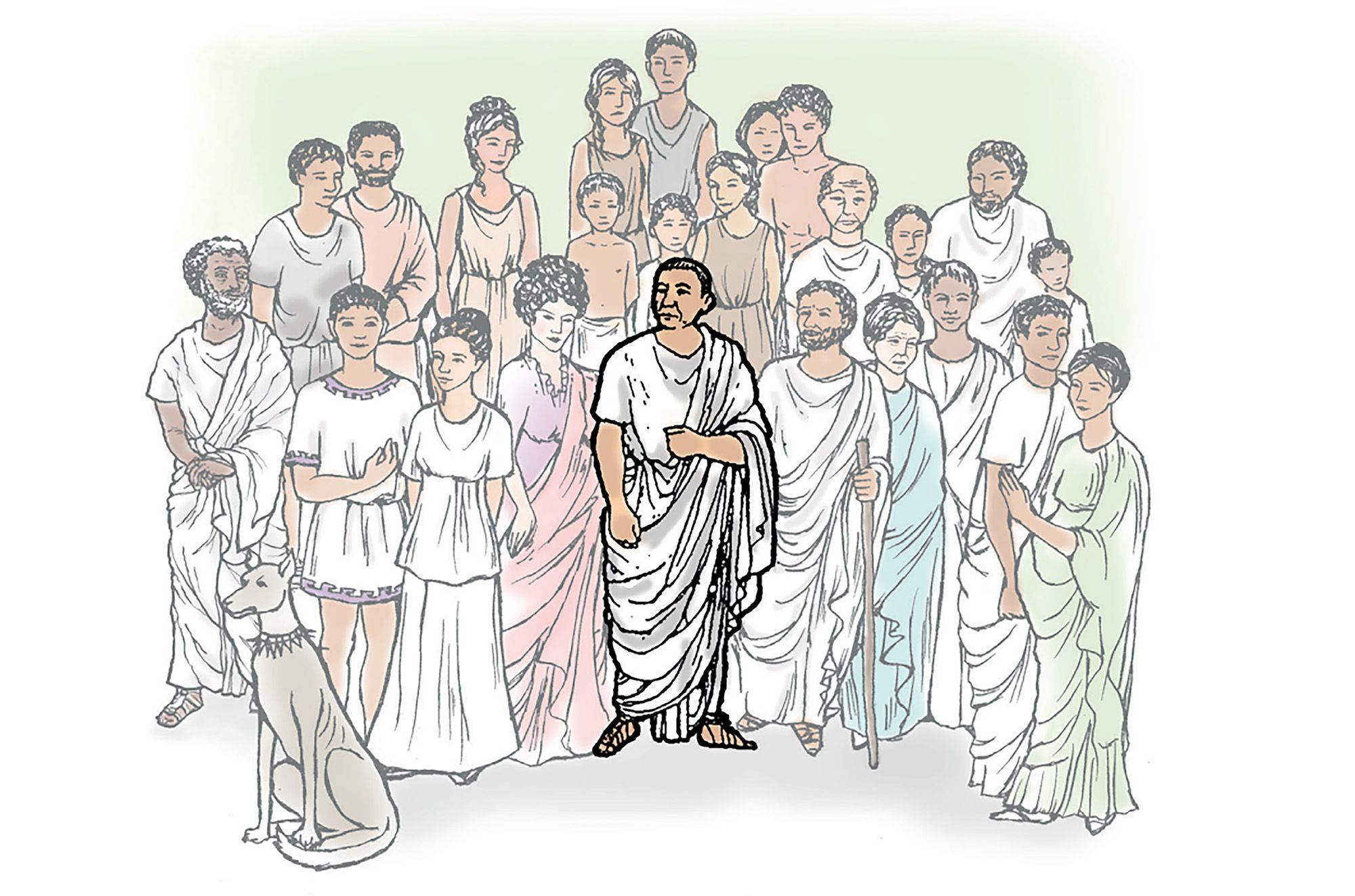

Characters from the Cambridge Latin Course, Book One. The iconic cast, recognisable to generations of Latin students, has been expanded in the new edition, partly in response to a need to improve diversity and representation.

Characters from the Cambridge Latin Course, Book One. The iconic cast, recognisable to generations of Latin students, has been expanded in the new edition, partly in response to a need to improve diversity and representation.

The newly-published fifth edition represents one of the most significant new editions in its 50-year history. It draws on a wider range of sources and on new scholarship to give a more accurate, evidence-based picture of the classical world. In doing so, it better prepares students to engage with classical works and to think critically about the past, while addressing concerns raised by teachers, academics and students about the representation of women, enslaved people, and minorities in the Roman world.

While the original cast are as central as ever, new characters have been introduced, stories rewritten and features updated. Women have greater prominence (Caecilius has a new daughter called Lucia, for example), readers learn more about the lives of enslaved people, and the multicultural reality of Rome’s vast, intercontinental empire is represented in greater detail.

The aim has always been to introduce students to the complexity of the Roman world and get them to think critically about it while learning Latin. The feedback we got told us we weren’t doing enough.

The course, which is written by the Cambridge Schools Classics Project at the University of Cambridge, was last revised in the 1990s.

The new edition has been informed by a fact-finding exercise in 2018 which involved school visits, surveys and interviews with hundreds of teachers and pupils. This confirmed long-held doubts about representation in the course books, prompting a thorough reassessment.

Caroline Bristow, director of the Cambridge School Classics Project, said: “The aim has always been to introduce students to the complexity of the Roman world and get them to think critically about it while learning Latin,” Bristow said. “That prepares them to engage more thoroughly with authentic classical sources. The feedback we got told us we weren’t doing enough in that regard.”

Girls were especially critical of the underuse of female characters. Metella’s infamous first appearance in the stories, in which she was passively “standing in the atrium”, symbolised how little they drove the narrative. “Girls had even started inventing their own backstories to compensate,” Bristow said. “It’s a bit heart-breaking when you’re a woman in charge of a course in which females are so under-represented the students are writing fan fiction.”

The stories in the new edition are, as ever, rooted in historical research, but expand women’s roles and devote more attention to their lived experiences.

Lucia, for example, is being pushed into an arranged marriage in Book One. Caecilius also hires a female painter, Clara, to introduce students to the fact that poorer Roman women had to work as well as men.

Bristow said: “We wanted to provide students with a more rounded picture of people and events, while ensuring the stories remain historically grounded. We’ve done that by drawing from that wider range of sources and events.”

This also helps to address the challenges that inclusion, access and minority representation can present for Classics educators. In particular, research highlights the imposter syndrome that people of colour feel when encountering the inaccurate, but standard, depiction of Rome as predominantly white. Other studies have shown that without being prompted to see diversity, even students of colour automatically make this assumption about the Roman world – a finding backed up by teachers’ experiences in the classroom.

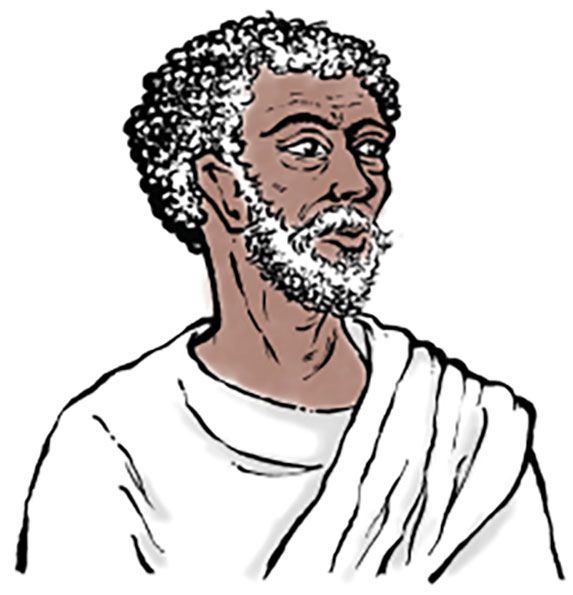

Responding to this, greater attention was given to cultural diversity in the new edition. For example, Barbillus, a wealthy Greco-Syrian merchant character, features more prominently and is clearly presented as a person of colour. His early presence in the stories is partly intended to challenge another general misconception, that such people were always enslaved.

Jasmine Elmer, a Classics educator and media personality whose work focuses on trying to broaden access to, and understanding of, the ancient past, was one of several experts who reviewed the new edition. “We’ve tended to take an all-white view of an empire that clearly wasn’t,” she said. “If you’re a person of colour, it’s natural to wonder whether people like you were even there. It’s a catastrophic failure of our subject and needs to be rectified. The new course seems to be braver about those issues. It doesn’t run away from complicated subject matter; it turns it into teaching points.”

Enslaved characters were, in earlier editions, sometimes depicted in simplistic terms: as “happy”, “hard-working” or “lazy”. In the new edition, slavery is now depicted through the eyes of its victims, focusing on their anxieties and gruelling lives.

It’s about inviting students to think critically about the past and its relationship to the present. That’s a valuable skill whether or not you end up doing Latin long-term.

Other changes reflect developments in historical scholarship since the series was last updated. Ingo Gildenhard, a Professor of Classics at Cambridge, advised the production team on a section on gladiators in Book One. Traditionally, gladiatorial combat has been presented as a strange, bloodthirsty aspect of Roman culture. Without ignoring its horrors, modern research nonetheless shows the reality was more complex: arena combat also stirred Roman audiences because it reinforced key contemporary values, such as martial prowess.

Teaching materials in the new edition draw attention to that more nuanced perspective. “It’s essential that instead of brushing aspects of Roman culture under the carpet, we look at it in the round,” Gildenhard said. “Part of this is about empowering teachers with new scholarship they might not have encountered. It’s also about inviting students to think critically about the past and its relationship to the present. That’s a valuable skill whether or not you end up doing Latin long term.”

Pupils and teachers have tested the new edition and responded positively. One young reviewer told the team: “I like that Lucia is educated, but I would like to know whether she actually wants to marry or not.” Of Clara, another commented: “It’s good that Caecilius is hiring women”.

Bristow said: “We sometimes get told that children just want to learn the language, study the amazing things Romans did and dress up as gladiators,” she said. “There’s lots that was inspiring, but this was a complex world. We’re teaching children to be Classicists. We’re not teaching them to be Romans.”

Five changes in the new edition of the Cambridge Latin Course

1. Caecilius’ family expands

The original ‘first family’ of the Cambridge Latin Course featured Caecilius, his wife Metella and son Quintus – plus their enslaved people and faithful dog (Cerberus). Research showed that girls taking the course felt the female characters were underdeveloped.

While characters such as Metella therefore have more agency in the new edition, one of the biggest changes is the introduction of a daughter, Lucia, whose character was successfully trialled in the North American version. Lucia’s presence enables greater exploration of women’s lived experiences. Students meet a young, unmarried teenager who has to grapple with being told her father intends to marry her off to an older man. She is also educated and passionately interested in Pompeiian politics.

Jasmine Elmer, a Classics educator and media personality who helped to review the new edition, said: “A lot of changes like this have been driven by the kids themselves. When we do a section from the fourth edition on Caecilius, for example, I often get asked, ‘What about Metella? What’s she doing apart from knocking around in the background?’”

2. Working women

Those women who did appear in earlier editions tended to be wealthy or enslaved. The new edition pays more attention to the lower classes of the ancient world. In Book One, Caecilius hires an artist, Clara, to paint a new fresco in his house. The character introduces students to the fact that many women had to work just as much as men. Clara – like most of the main characters in the course – is based on a real-life historical figure, who in this case crops up in Pliny. Caroline Bristow, director of the Cambridge School Classics Project, said: “Clara helps us to reflect more of the nuances that defined women’s lives. It’s true that some elite women worked purely within the home, running the household and raising children. For the poor women of the Roman world that wasn’t really an option.”

3. Barbillus updated

Barbillus, a character who originally appeared in Book Two, is a successful Graeco-Syrian merchant who lives in Alexandria: a complex, cultural melting pot in the First Century, when the stories are set. Line drawings in earlier editions failed to convey his heritage and ethnicity, but in the new version he is clearly a person of colour. He also first appears earlier in the saga, in Book One, to help address misleading depictions of the Roman world as predominantly white, and similarly popular misconceptions that all people of colour were enslaved.

“People of colour may have been enslaved, but what about those who were not?” Elmer said. “What roles did they take up in society and what did life look like for them? We need to challenge the widely-held belief that Rome was an all-white society. Quite frankly, it just wasn’t.”

4. A tough life for enslaved people

Students also wanted to know more about enslaved characters. They were also often described in terms such as lazy, happy, or loyal – a hangover from the traditional, over-simplistic representation of Rome as a ‘civilising’ force in the ancient world. “Quite often their main aspiration in life seemed just to be a good enslaved person, which is clearly unrealistic,” Bristow said.

The new course develops enslaved people’s characters and, in particular, explores their anxieties and the arduous nature of their lives. Students are encouraged to think critically about the contrast between being enslaved and being free. Research showed that this more detailed approach to the lives of enslaved people – for example, examining what they ate and where they slept – provoked students’ curiosity and desire to find out more.

5. Gladiators reappraised

Gladiators are an iconic feature of the Roman world, not least thanks to Hollywood blockbusters from Spartacus to Ridley Scott’s eponymous box office hit in 2000. How we understand the phenomenon has, however, changed. Professor Ingo Gildenhard, who provided expert advice for the new edition, points out that while in the 1950s and 60s gladiatorial combat was presented as “something revolting and horrible that we couldn’t possibly understand”, more recent scholarship takes a more nuanced view. “People have begun to ask, ‘OK, no culture does anything without a reason, so did the Romans really just enjoy this because they were all sadistic?’” he said. “We rightly condemn it now, but these people were put on display to enact core Roman values – like bravery or fighting skills. Those ideas probably shaped the viewing experience for most Roman spectators.”

Starting with this point, the new course encourages students to use what seems like a deeply foreign aspect of the past to reappraise the present. “Having helped students to understand what Romans got out of it, it’s possible to start a discussion that reassesses exactly how strange this idea is,” Gildenhard said. “The way people enjoy boxing, for example, is not so far removed from how the Romans saw gladiatorial combat.”

Images in this story are all from Book One of the fifth edition of the new Cambridge Latin Course.